History is full of butterfly effects. The first voyage of the Dutch to China is no exception, thanks to the Portuguese.

During the Eighty Years’ War — the Netherlands’ struggle for independence from Spain — the Dutch faced increasing hostility in overseas trade.

First, the Spanish closed all their ports to Dutch ships. And after Portugal fell to the Spanish in 1580, all Portuguese ports closed down too.

Why did the Dutch go to China?

As a result, the supply of spices to Amsterdam came to a halt. Driven by the love for spice and money (and probably also the adventurous spirit of the Age of Discovery), the Dutch decided to find their own way to Asia, with China as one of the top destinations.

But why China? The tremendous fascination for the Chinese can (at least partially) be credited to two men who sailed to Asia while in service of the Portuguese: Jan Huygen van Linschoten and Dirck Gerritszoon Pomp.

Van Linschoten, who stayed in the East Indies from 1583 to 1589, gathered as much information about the Asian countries as possible. He published his travel book Itinerario naer Oost ofte Portugaels Indien upon his return.

His reporting on China was, funnily enough, based on the work of a Spanish priest Juan Gonzalez de Mendoza, who had never been to China, and used information from Augustinian and Dominican preachers who had.

Nevertheless, it sang praises of the Chinese goods, spurring the Dutch interest in the Far East.

From Dirck Gerritszoon Pomp to “Dirck China”

Dirck Gerritszoon Pomp had visited Macau several times and could not stop talking about its wonders after returning home. He also spread the word of the ridiculously lucrative trade the Portuguese were doing there.

Gerritszoon Pomp revealed that the most profitable trade in Asia was between Asian empires, with the Portuguese as middlemen. He even got a nickname for his enthusiasm for the “land of tomorrow” — “Dirck China”.

The barter of Chinese silk for Japanese silver yielded particularly great treasures. The Portuguese situated in Macau would stock up on Chinese silk and gold (which were in high demand in Japan) and exchange them for cheap silver in Nagasaki before returning to China to trade the silver for silk and porcelain to bring back to Europe.

READ MORE | Lost in translation: a hilarious history of Chinese porcelain in the Netherlands

The exchange of goods through the Asian ports yielded so much revenue that the purchase of spices for Europe could be financed by the profit made along the way. Understandably, China became one of the top destinations for the Netherlands.

Finding the way

Seeing that the Portuguese were under Spanish rule and the Dutch were at war with Spain at the time, the Dutch wisely chose to avoid the Portuguese routes and find their own way to Asia.

It took some failed attempts, including the famous “Nova Zembla” incident, where a crew tried to go through the Arctic but got stuck due to sea ice. Their story lives on in Dutch national history as an example of perseverance and heroism.

However, one voyage to the city of Bantam on the west coast of Java proved to be a breakthrough. According to Jan Huygen van Linschoten, Bantam — whose pepper production attracted many Chinese merchants — had no Portuguese occupants.

Upon arrival, however, the leader Cornelis de Houtman was greatly disappointed that there were already Portuguese merchants there, eyeing them suspiciously.

Still, a silver lining came in the form of wealthy Chinese merchants living in their own “Chinatown” outside the city walls. They treated the Dutch crewmen with hospitality and could tell them all about their hatred of the Portuguese merchants.

Even though this journey resulted in heavy losses — both in human life and goods — the Dutch were proud to finally have found their own way to the East Indies. However, too much competition in Asia meant that the Dutch needed to find a settlement as close to China as possible.

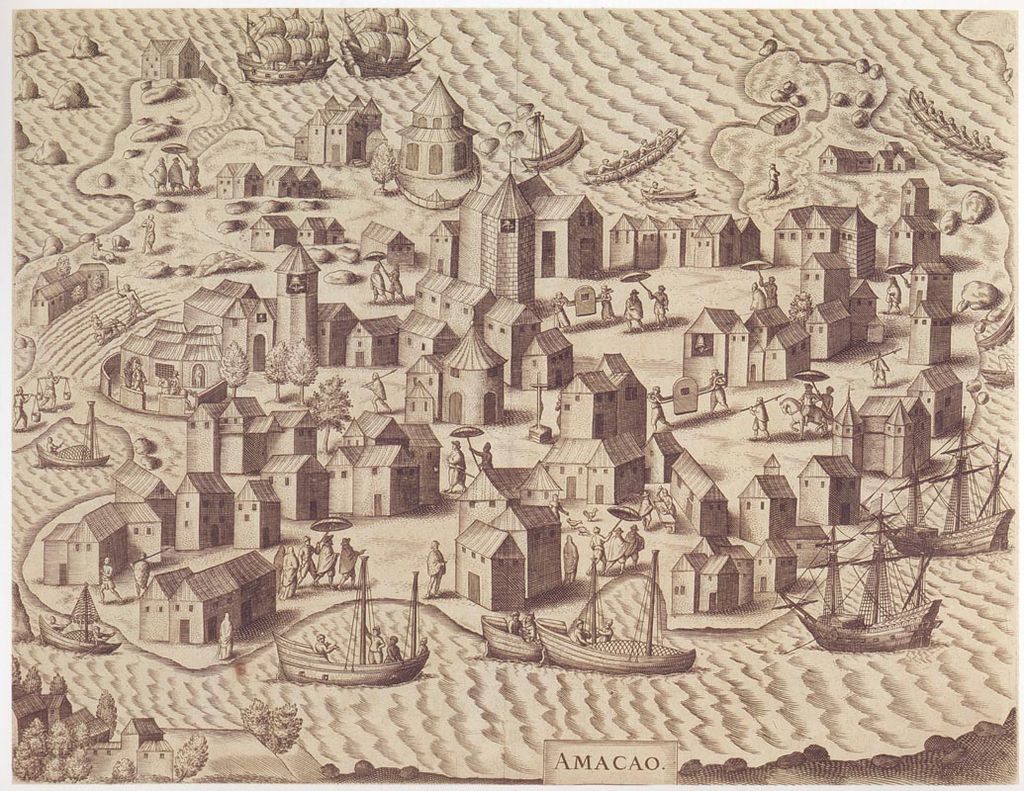

In the end, the Dutch set their eyes on Macau in the Pearl River Delta, where the presence of the Portuguese was, at best, tolerated by the Chinese Ming dynasty.

Meeting in Macau

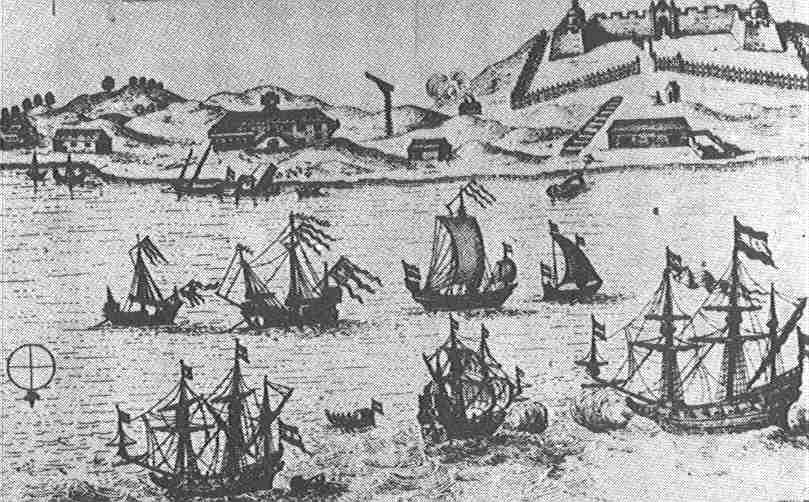

On June 28, 1600, a fleet of six ships set sail to the East Indies under Admiral Jacob van Neck’s command. Initially, they intended to send two ships to China after arriving in the East.

READ MORE | Dutch quirk #120: Struggle with their colonial past

However, due to bad wind conditions in South and Southeast Asia, they decided to head straight for Macau, where they could stock up on provisions and gather information about their trade.

After some struggle with the notorious typhoon on the Chinese sea, Van Neck was, with the help of some Chinese fishermen, finally greeted by the sight of Macau — “a large city, built with Spanish fashion… on the mountain stands a Portuguese church with a giant blue cross.”

Shortly after their arrival, they sent a small boat carrying some sailors to the city. The moment the crew set foot on Chinese soil, they were arrested. A day later, another boat was sent to find a better anchor point and was captured.

A total of 20 sailors disappeared into the mouth of Pearl River, never to be seen again. Except for one — Maarten Aap, who returned to the Netherlands several years later.

Any attempts to retrieve the lost crew were futile. Van Neck was deeply frustrated and thought the Chinese were barbaric for imprisoning his men without any warning. However, the truth, as history has taught us time and time again, is never that simple.

The tragic faith of 17 Dutch sailors

At the end of the sixteenth century, the Chinese Ming government had developed somewhat of a “love-hate” relationship with the Portuguese. On the one hand, the speedy growth of the Portuguese settlement was seen as a threat.

On the other hand, The Ming government needed the Portuguese for their “divide-and-conquer” strategy — the Portuguese received advantageous trading deals while other countries didn’t, leaving the Portuguese to deal with jealous competitors.

So, it was no surprise that when the strange newcomers arrived in Macau, the Chinese officials and the Portuguese had opposite reactions.

The Portuguese, who arrested the Dutch sailors, wanted nothing more than to remove these protestants threatening their trade monopoly.

Meanwhile, Chinese authorities wanted to speak with the new foreign merchants and offer them a piece of land elsewhere at the mouth of the Pearl River. That might turn them into enemies of the Portuguese and, hopefully, lead to greater conflicts in which both sides would lose.

Alas, the Portuguese were too quick to take action. When the local authority ordered them to hand over the Dutch sailors as soon as possible, 17 sailors had already been hanged by the Portuguese, while the remaining four were sent to Goa. Not even converting to Catholicism convinced the Portuguese to spare their lives.

The Portuguese also sabotaged Chinese attempts at communication with the Dutch ships, either through translation or bribery. On October 3, Van Neck finally decided to turn back without the imprisoned sailors.

Throughout the whole ordeal, the Chinese learned nothing of the Dutch except for their appearance, describing the event as such:

“In September 1601, two barbarian ships arrived in Macau. Even the interpreters didn’t know from which country they came. People called them “red-haired devils.” Their hair is reddish, and their eyes are round.

They stand at about ten feet, seemingly as strong as the barbarians of Macau (the Portuguese). Their ships were huge and covered with copper plates, sinking twenty feet into the water.

The barbarians of Macau were concerned about these potential competitors in trade and drove the ships out to the Pacific Ocean by force. The ships were then blown away by a typhoon. There’s no way to know where they ended up.”

Heemskerck’s revenge

Well, so the first voyage to China turned out to be a complete failure. The ships returned with fewer goods, fewer men, and a whole lot of rage. A year later, the Dutch finally learned of the fate of the imprisoned sailors.

In April 1602, Admiral Jacob van Heemskerck (leader of that Arctic exploration) captured a Portuguese ship off the Javanese coast and discovered documents detailing the murder of the 17 sailors.

Furious, Van Heemskerck swore to avenge his fallen countrymen. He stayed true to his vow when he captured the Portuguese carrack (meaning merchant ship, kraak in Dutch), Santa Catarina, on February 25, 1603, which was fully loaded with Chinese silk and porcelain from Macau.

The cargo was then auctioned off in Amsterdam and brought in over 2.5 million guilders. Since then, Kraak Porcelain has become a household term in the Netherlands.

The hijacking of Santa Catarina, however, attracted international attention and set off a ripple effect in the course of global history. It marked the start of the Dutch–Portuguese War, which would end with the Dutch overthrowing the Portuguese monopoly on trade in the East Indies and establishing colonies in Indonesia that served as bases for colonial advancement in China.

Unfortunately, news of the hijack wasn’t well-received in China. After the first encounter in Macau, the Portuguese told China that the Dutch “red-haired devils” were all barbaric pirates who didn’t deserve mutual trade. The Chinese were initially suspicious of their words but changed their mind when they caught wind of the hijack.

Little did the Chinese know they would be dealing with more “barbarians” than just the Dutch as a result of this hijack. The auction of Chinese goods was an eye-opener for many European merchants. Until that point, the Portuguese had kept their trading activities in Asia a secret.

However, the selling of the Santa Catarina cargo made many Europeans realize the enormous profits that could be made in Asia, especially in China. Following this, foreign traders and colonialists started to plague the coasts of China.

As for the Dutch, their bad reputation led to a century of conflict with China. Failed attempts at mutual trade resulted in invasions with twists and turns, which inevitably dragged both countries into the ever-growing monster that is the global trading system.

Did you know about this interesting chapter in Dutch history? Tell us in the comments below!

Feature image: Aert Anthonisz/Wikimedia Commons/Public Domain

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in April 2021 and was fully updated in August 2023 for your reading pleasure.

Very interesting

Interesting read