The Province of Drenthe lies like a mysterious, empty middle pocket in the centre of the Netherlands, often overlooked by both tourists and even Dutch nationals alike. Almost no one visits.

It’s no wonder Drenthe is where you’ll stumble across the iconic hunebedden, the huge, grey stone burial chambers built amidst the bogs and peat by ancient tribesmen as early as 3000 BC, structures which predate even Stonehenge in England.

As legend proclaims, the prehistoric giants peacefully repose here. But sleepy Drenthe is also known for something much more modern and infinitely more sinister: the Westerbork concentration camp, from whose gates more than 100,000 Jews – including a Dutch girl named Anne Frank – were deported from the Netherlands to their deaths during World War II.

Westerbork is a story few know and fewer actually visit. It’s a part of Dutch history which is so sad and so horrific than even Dutch citizens hardly ever go – and, since even fewer international tourists discover Westerbork, even the small museum’s exhibits are explained only in Dutch, not even English.

About Westerbork concentration camp

I went to Westerbork last summer. It was not easy to find. It’s outside the small Drenthe town of Beilen, which is one train stop south of Assen. There were no road signs or tourist markers or easy-to-follow directions. It’s solemn and quiet and slightly depressing.

When you arrive, you pull into a small parking lot with a modest, unpretentious museum and restaurant at the camp’s far boundary. You are told it’s either a long walk or a shuttle bus ride to the actual camp and you’re given a time when the next shuttle leaves.

While you wait, there is a small museum dedicated to an overview of the Holocaust, the story of Westerbork and a focus on the Anne Frank story as a microcosm of the nearly complete destruction of the Dutch Jews. Almost everyone knows Anne’s tragic life, how she and her family and a small group of friends hid in a secret annex in Amsterdam on the Prinsengracht, hiding for almost 2 years in a secret attic hideaway.

But Westerbork tells the next chapter in Anne’s life, one which almost no one knows: her brief stay at Westerbork before being transported to her ultimate death at the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp in Germany in 1945.

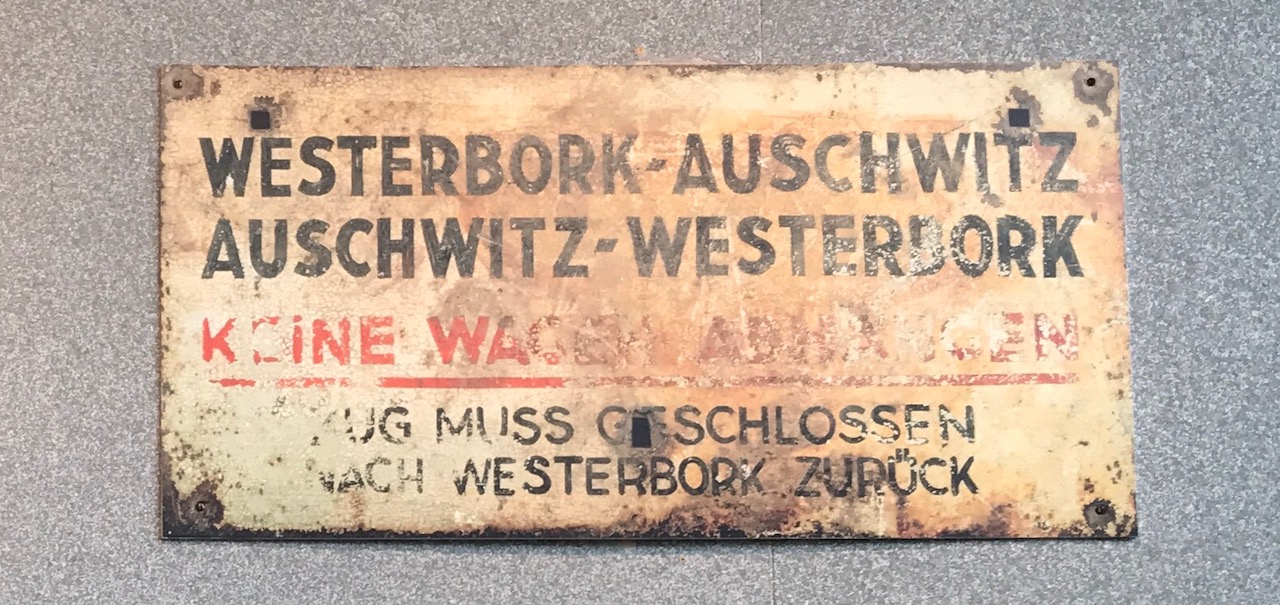

The museum seems tired and depressed in its own way, sort of like a 1950s museum which has never been updated. Despite the tired presentation, these are powerful exhibits because the subject matter is so powerful; you’ll see artefacts recovered from the camp, testimonials from survivors, and photographs and exhibits depicting camp life.

It’s a very old-fashioned and worn down museum, and all of the audio and signage is in Dutch. Fortunately, I understand rudimentary Dutch, but I felt dissatisfied with the presentation; my Dutch friend opined that maybe it’s a museum ONLY for the Dutch and not for those who aren’t fluent in the Dutch language. Luckily, there is an accompanying bookstore which has a variety of books in both Dutch and English, including copies of Anne Frank’s iconic diary.

Despite not being able to read or grasp the full story, it’s clear that the story here is beyond grim. It’s unimaginable. But true. What happened here is so awful it tests the boundaries of human understanding.

A historical recap:

Westerbork concentration camp was, ironically, constructed by the Dutch government in 1939 as a haven for a tidal wave of German Jews fleeing the rising tide of antisemitism in Germany and the ultimate grasping of power by the Nazis which precipitated World War II. While almost all of the original buildings are now gone, you can still get a sense of the boundaries, the square grid layout of the barrack type buildings and the railroad tracks leading to death – one line in, one line out – haven’t changed.

When the Nazis invaded the Netherlands in May of 1940, they found another grisly use for Westerbork: a prison camp for Jews and other “undesirables.” In 1942, Westerbork became the way-station to death, the place where Dutch Jews who were victimized by the Nazis were assembled in the remote countryside of Drenthe before being transported on fatal train rides to death camps deep into Eastern Europe such as Auschwitz in Poland.

What to expect at Westerbork?

A long walk, or short bus ride, leads you to the concentration camp itself down the road. And, while almost all of the original buildings have been dismantled and are now gone, there are several original structures set up as monuments or landmarks along the way to give visitors a sense of when Westerbork flourished.

Now, this is a very ominous ghost town. You learn that Anne Frank and her family were designated upon arrival to reside in the “Punishment Barracks,” and in your mind, you can hardly process what the term “punishment” means in the context of a Nazi concentration camp. But, she survived what must have been a truly horrifying experience and, with her sister, endured Westerbork only to await even grimmer future experiences after leaving.

You’ll see outlines of buildings designated as workshops where Dutch Jews were virtual slaves and the Kommandant’s house is preserved – enclosed in glass like a greenhouse, a testament to evil.

Next to this house are informational signs, like billboards, enlarged photos of the various commanders of Westerbork with a synopsis of their various evil deeds, including one smiling, blonde commander who personally executed several hundred prisoners with his handgun. Yes, I said several hundred. It is hard to absorb.

Other monuments include the twisted railroad tracks leaving the camp toward Poland, and a huge memorial of small stones representing the thousands of individual victims who came and went, never to return. And, always, you are aware of the threatening barbed-wire enclosures which surround you and symbolize the feeling of entrapment.

One lone representative guard tower looms, a monument to oppression, and visitors today can only use their imagination to try to feel what it must have been like to be a prisoner at Westerbork concentration camp, the terror, the hopelessness, the fear.

The Aftermath

Most tourists come to happy Holland to cruise the canals on a tour boat, or view the glorious tulip fields at Kuekenhof, or enjoy the iconic works of Rembrandt, Vermeer and Van Gogh in amazing museums and art galleries. The Netherlands is such a beautiful, tolerant and peaceful place. It’s why I keep coming back, year after year. Ik hou van Nederlands!

But, even in the sunny tolerance and peacefulness of this wonderful land, it’s important to understand the full history and appreciate the good days we currently have. The Westerbork concentration camp is such a place. We must never forget that. Tot ziens!

Liking this article? Be sure to follow DutchReview on Facebook! Or subscribe to our Youtube or Instagram account!

Feature Image: Bert Kaufmann/Flickr

Great piece Alex. My grandparents died in Auschwitz, and a kind young Dutch girl – Doris Katz – spent two years forwarding their letters from Nazi Germany to my own mother (who had escaped to the UK). Doris was eventually rounded up, sent to Westerbrook in Feb 1943 and then on to Sobibor where she died early the following month. I knew little of this Dutch way-station to death and your article is v helpful.

Hi mr Katz

Familiar name in Drenthe

I am born 20 minutes from this camp

(12 years after the end of the war)

We even helped taking apart the buildings and with the boards build a shed near our farm

My name is Henk Enting

I am living in Manitoba Canada Since 1998

I’ve played in this camp as a child with friends

But, I have never heard of these multiple personal executions before. Not that I wouldn’t believe it. But ppl in the area probably didn’t know that fact so clearly.

Or perhaps are somewhat ashamed of the very fact this could all happen so close to home

If you wouldn’t mind, I’d appreciate it very much if and when you find details, you forward such to me

If you like to I can give you email address.

I’d like to know more about the German guard who shot hundreds of people in Westerbork. This is not something I’ve read about in regards to Westerbork on any other site. Thank you

Alex: as per my question, above and your quote, “ Next to this house are informational signs, like billboards, enlarged photos of the various commanders of Westerbork with a synopsis of their various evil deeds, including one smiling, blonde commander who personally executed several hundred prisoners with his handgun. Yes, I said several hundred”. Can you post this picture or give this man’s name so I can research myself? As I said, this story is new to me AND I’m currently discussing Westerbork with the grandson of a former guard who disputes more than a few executions took place at this camp. Thank you.

Yeah Victoria, sure… of course the grandson will dispute anything that the Nazis and their collaborators did to the victims, wouldn’t you if it were your grandfather who was guilty of such despicable crimes carried out against the victims of the Nazis. The grandson might be thinking that if he downgrades what his grandfather did, in his mind he might think that ppl wouldn’t see him in a bad light, but whether he personally killed victims or not is neither here or there, his grandfather was a collaborator and a nazi himself, their ideology and skewered beliefs were and are still mind-boggling, your friend’s grandfather was a war criminal from a war that obliterated the Jewish community in Europe AND other communities, the Roma, Sinti, etc and anyone who got in their way. And the grandfather isn’t going to admit to his family or friends exactly what he did. He sounds like a man that has plenty to hide.

Hello Alex, I enjoyed your story on Westerbork. as well as the photos. I was only 6 years old when my mother and I were loaded into a truck at the market place in Apeldoorn, and , along with other jews were sent to Westerbork.

My father had been taken in 1942 and sent to Frankfurt am Mein, so it was just my mother and I. I was too young and too confused as to what was happening, so I had to rely on my mother on the story of what occured…as it happened, we were in Westerbork 5 days, and the war was over, so we returned to Apeldoorn. Thank G-d we came out alive.

My mother and I moved to Canada in 1947, where my mom passed on, but of course we never forgot this terrible page of our lives.

My grandma had a first cousin Izak Meijer Turschwell , who was arrested 19 August 1942 in den Haag . After two days at Westerbork, cousin was sent to Auschwitz. In January of 1945, cousin was transported to Buchenwald. It was 6 February 1945 that he was further transported to Camp Wille….there the trail ends. I would sure like to know if he survived.

I was born in den Haag after the war. What is mind boggling is that where cousin lived in den Haag was only four miles from where we lived in Wassenaar. We went to the States to live in 1956. Papa and other cousins told me about relatives that were shot in Poland in 1942.

I am watching Steal A Pencil For Me. My heart breaks so badly that I can hardly breathe.