The Eighty Years’ War or the Dutch Revolt, is a standard part of Dutch history education. Almost every Dutch person or history buff has heard of the Battle of Nieuwpoort, the beheading of Johan van Oldebarneveldt, the murder of Willem van Oranje and the Twelve Years’ Truce. All of these historical events played a major role in shaping the Netherlands and making her what she is today – a liberal and tolerant country with a Calvinist nature and a complicated history/relationship with clandestine churches.

The Habsburg and Spanish Netherlands

The Netherlands did not exist in the 16th century. The areas that today, are roughly the Netherlands, Belgium and Luxembourg once belonged to the Habsburg Empire of Charles V and were called “Seventeen Provinces”. The Habsburg Empire also consisted of Spain, southern Italy and large parts of Central Europe. As a result of different decisions made by Charles V over the course of his rule, the Netherlands increasingly leaned towards forming an autonomous state, which theoretically fell under the Empire and with Charles himself at the helm.

In 1555, King Philip II of Spain succeeded his father as ruler of the Netherlands. During his rule, the Netherlands was neither a country nor a united region. It was just a collection of autonomous city-states with little evidence of a sense of cultural solidarity. In 1559, Philip left the Netherlands and appointed his half-sister Margaretha of Parma as governor.

Religious Conflict (Iconoclastic Fury)

The main source of friction between the Habsburg ruler and the Netherlands was undoubtedly religion and it acted as fuel and matches that lit up the fire of the Eighty Years’ War. A fire which would rage throughout the old lower countries. To the Catholic Spaniards, the Protestant Dutch were ‘heretics’ and in his fight against them, Charles V issued the so-called ‘blood placards’ in 1550, which stated that writing, distributing and possessing heretical books and images, attending and preaching during Protestant meetings or housing Protestants with was to be punished with death. The Catholic rule of Philip II was intolerant and that infuriated the Protestant Dutch even more.

Not all Dutch folks were Protestant though, and many Dutch Catholics sympathised with their persecuted neighbours, who often had to practice their faith in secret. As a result of the persecutions, executions and economic malaise, more and more Dutch folks converted to Calvinism. While he may never have set foot in the Netherlands, John Calvin’s teachings found fertile soil in the lower countries. Margaret of Parma did not know what to do about the widespread embrace of the teachings of a French Protestant, and temporarily suspended the prosecution and execution of Protestants. That decision led to the Beeldenstorm or the Great Iconoclasm of 1566. During these spates of iconoclastic fury, Catholic art and many forms of church fittings and decoration were destroyed in mob actions by Calvinist Protestant crowds as part of the Protestant Reformation. With the destruction of Catholic images and art, the Dutch dissatisfaction with the Catholic Spanish rule had been turned into full violence and thus, the start of the Eighty Years’ War.

Willem van Oranje

In the run-up to the outbreak of violence, several Dutch nobles, including Willem van Oranje, had already tried to appease the situation by requesting the Spanish monarch to establish freedom of conscience and religion and to suspend the persecution and execution of Dutch Protestants. The funny thing is that Willem van Orange was a loyal servant of Phillip II and had thought that the situation could be salvaged by talking to the Spanish monarch. Unfortunately, talking to him didn’t help. Once the Iconoclastic Fury broke out, several nobles openly supported Protestantism and the opposition to Spanish rule. When the Duke of Alva, the new governor of the Netherlands, arrived in Brussels in 1567, many of the Dutch noblemen who were in support of the Iconoclastic Fury were imprisoned or tried and convicted in absentia. A year later, Willem van Oranje, along with his brothers Lodewijk and Adolf van Nassau, delivered the first defeat against Alva at the Battle of Heiligerlee.

Amsterdam during the Eighty Years’ War

Amsterdam was taken on May 26, 1578. In the course of the war, Willem van Oranje desperately wanted Amsterdam to join his resistance against the Spanish but the city’s officials stubbornly remain loyal to the Spanish due to the fact that they were Catholics. Willem van Oranje wasn’t going to have any of that. On that fateful May day, a group of former exiles, Dutch nobles and armed Calvinists blocked the Dam Square. Subsequently, more than twenty members of Amsterdam Catholic City Council were evicted from the city hall via barges on the Damrak. The widely despised Franciscans were also removed from the city. Finally, Amsterdam was won by the insurgents via a bloodless coup.

Although the Golden Age is widely known as a century of tolerance, that tolerance did not apply to non-Calvinists. If you were a Catholic or a Lutheran, you had freedom of conscience and freedom of religion – as long as you practice your faith in the secrecy of your home. After the Calvinists seized power in Amsterdam, the city’s Catholic government was deposed and three days later a new council was installed, consisting of thirty Calvinists and ten Catholics. The event became known as the Alteratie or Alteration of Amsterdam.

After the Alteration, the Catholic Houses of worship came into the hands of Protestants and were given new names. The Sint Nicolaaskerk thus became the Oude Kerk and the Heilige Stede was renamed Nieuwe Zijds Kapel. Monasteries also came into the hands of the Calvinist City Council. On May 28, two days after the change of power, the first Reformed worship was held in the Old Church. The general idea was that every Dutchman or woman was supposed to be Reformed. The lack of recognition for other Christian denominations gave birth to small clandestine churches in different parts of the country.

Clandestine Churches

A few months after the Alteration, Catholicism was officially banned in the city. In Zwolle for example, Catholics were prohibited from living next to each other! Only foreigners were allowed to openly worship, so Jews never had a problem. Due to the fact that Catholics could no longer openly worship, some small shelters were set up in different parts of the country. These shelters were called clandestine churches which were, in theory, an unrecognisable church building, where religious folks who weren’t Protestants secretly came together to worship. The buildings were “disguised” like a house or a farm and was carefully designed not to reveal their purpose. If it was too obvious that it was a Catholic church, the owner of the building was fined or punished. The most famous clandestine church in the Netherlands is Ons’ Lieve Heer op Solder in Amsterdam. This old church on the Oudezijds Voorburgwal, nowadays a museum, was built by Jan Hartman, a German Catholic merchant. In 1661, Jan Hartman bought not only the canal house on the Oudezijds Voorburgwal but also the two houses behind it. He had the top floors of the three buildings connected and that’s where the church was built. The chapels and church are still intact and can be visited anytime.

Tolerance in the Netherlands

In the old Republic of the United Netherlands, citizens were entitled to freedom of religion and freedom of conscience. Willem van Oranje laid the foundation for this in the sixteenth century. The clandestine church/Museum Ons’ Lieve Heer op Solder illustrates the way in which people in the seventeenth century dealt with various religions in Amsterdam. The museum shows how Catholics lived in a time when they couldn’t openly practice their faith. Catholic Amsterdammers were not allowed to celebrate mass in public but were allowed to worship however they saw fit in the confines of their own homes. Even Lutherans and Mennonites also had to worship in their homes despite being Protestants. This raised questions about the liberal values of the Netherlands and how truly free her people were.

As the years passed, the Calvinists became more tolerant towards Catholics and other arms of the Protestant movement, as well as people of other faiths. The Calvinist government soon realised that it was impossible to force people to join the Reformed Church and they responded by taking ‘baby steps’ towards remedying the situation. Catholic churches were allowed to pay ‘recognition fees’ in order to obtain an official permit. The recognition fees were a huge amount of money, which did not give Catholics access to many rights. Clandestine churches no longer had to conceal their religious practices. Moreover, the Catholic faithful were not allowed to enter their church buildings via a public road and church bells were totally out of the question.

Freedom of Religion

In the end, the arrival of the French at the end of the 18th century led to the introduction of religious freedom. The Catholics were allowed to build real churches and freely worship in the open again. However, many clandestine churches still remained in use for a long time, especially in the west of the country. Unfortunately, most clandestine churches were either demolished or rebuilt as apartments, houses, etc. Some of them housed so much history and were filled with interesting stories about a time of religious strife in the Netherlands.

Although the Netherlands isn’t really a religious country like she once was, the country still has around thirty clandestine churches of which Ons’ Lieve Heer op Solder is the most visited one by tourists. If you’re ever in Amsterdam, make sure you pay a visit to these old and interesting clandestine churches. They are an embodiment of Dutch history and interestingly illustrate the lower country’s identity crisis. Her journey to discover herself and lay the foundation for what would turn out to be the tolerant Netherlands that we know and love today.

Have your ever been to Ons’ Lieve Heer op Solder? Let us know in the comments.

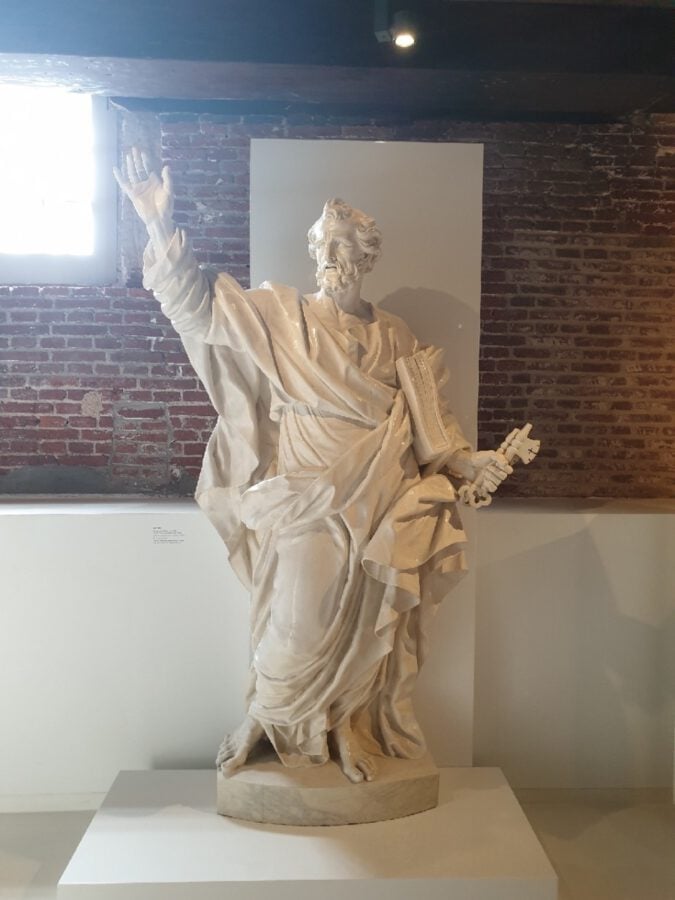

Hello, wonderful article. I noticed an error however. You show a photo of a statue that you call a statue of Jesus Christ. That is wrong. The statue depicts St. Peter, holding the keys to heaven.

With Corona and in response to the loud appeal of social justice worriers worldwide money and interest is shifting away from these important symbols of oppression of the Catholic community in the Netherlands.