On July 1, 1863, the Netherlands abolished slavery in Suriname and the Netherlands Antilles. In the Netherlands, the impression is often that slavery is an American and British concept, a period when both nations traded in, and transported shiploads of people from Africa to the American continent.

The fact of the matter is that the Netherlands also has several centuries of slavery history which Dutch teachers are often scared of teaching their students, white Dutch folks are very uncomfortable to talk about, and the chapter in history is almost completely ignored to date by the Dutch government.

READ MORE | Controversial slave panel could lead to the retirement of the Golden Carriage

How is it that this integral part of the Dutch past is completely missing from our collective memory, in our national history, in our education, in our political discourse, and in our national commemorations?

In these weeks leading to Keti Koti (an annual celebration on July 1 that marks Emancipation Day in Suriname), let us take a peek into the lives of slaves in the Dutch colonies.

Let op! We’re talking straight in this article, so there are accounts of torture that some readers may find graphic or troubling.

The Dutch as slave traders

The Dutch contribution to slavery is, to put it mildly, a less glorious part of Dutch history. Suriname, which was a former Dutch colony, was known to have the reputation as a place where slave owners treated their slaves the worst. It’s not that much of a secret that the Dutch slave masters were really more cruel than the British, French, Portuguese and Spaniards.

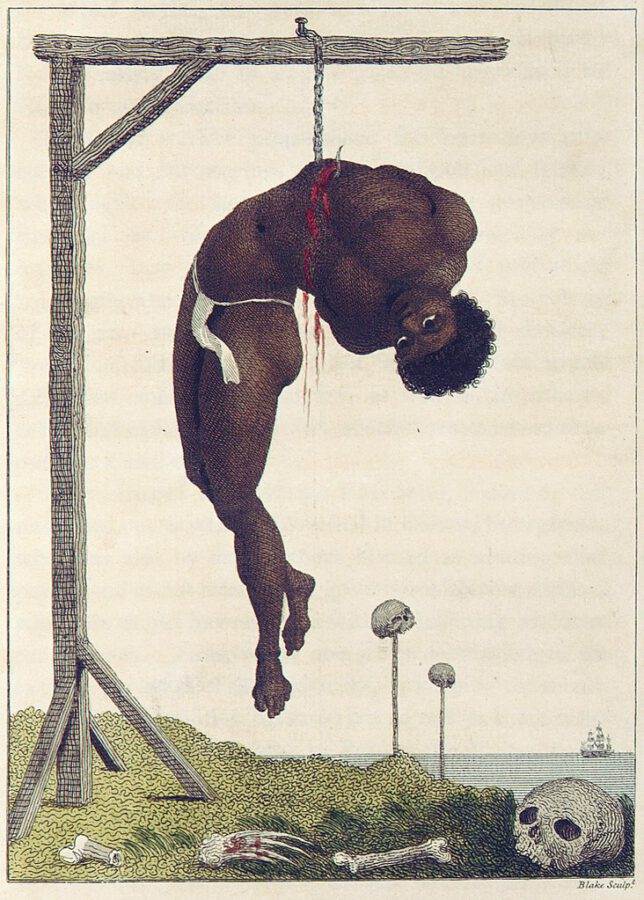

To illustrate the barbarity of slavery in the Dutch colonies, one picture that comes to mind is that of a slave hanging from the gallows with an iron hook through their ribs, while in the background are a set of skulls rested threateningly on stakes.

A first-hand account

This engraving by William Blake is based on a story that captain John Gabriël Stedman heard and wrote in Suriname. John Gabriël Stedman was a Scottish-Dutch officer in the Scottish Brigade of the Dutch Army who had volunteered in Suriname for an expedition to quell the revolt of runaway slaves, the Maroons.

During his time there, he was taken aback by the cruel treatment of the slaves at the hands of their masters. He ended up falling in love with a slave girl, and at one point, tried to buy her freedom. He wrote the influential book the “Narrative of a Five Years Expedition against the Revolted Negroes of Suriname”. In this book he was openly concerned about the rights of the slaves, in particular whether they should be treated as human beings.

Stedman’s book which was published in London in 1796, is an account of the impressions the 28-year-old captain gained during a five-year stay in Suriname. The artist and poet William Blake made engravings, based on his stories and drawings which depicted the cruelty of the slave masters.

For example, he describes how a certain Mrs. S. was fed up with the crying of a slave’s baby: “Mrs. S. ordered her slave girl to bring the child to her. She then took the child by one arm, held it under the water until it drowned, and then she threw it into the stream.” After the mother tried in vain to save her child, she was mercilessly whipped for disobedience.

It will come as no surprise that after the publication of this book, Suriname gained the reputation of being the colony with the most repulsive form of slavery.

Not human but merchandise

From the end of the sixteenth century, Dutch merchants, especially the Hollanders and the Zeelanders (Zeeuwen), had become heavily involved in the Transatlantic slave trade. After about 1635 the West India Company (WIC) also joined in the slave trade.

Slaves were a lucrative commodity; after all, the plantations that the Europeans had built in the “New World” needed labour, and to them, what was better than free labour from Africa?

When the Caribbean region — unlike areas like Peru and Bolivia — turned out to contain little gold and silver, the Spaniards and eventually, other Europeans soon found a way to try to make a profit from the “newly discovered” territory.

New crops such as sugar, coffee and cotton were introduced from Asia and the Middle East, which had to be grown on a large scale in the tropical climate to fill their home country’s treasuries. A lot of workers were needed for this.

The original inhabitants of the area were unsuitable for the hard work and, moreover, had almost been exterminated by the white invaders through massacres and the diseases they brought from Europe. It was therefore decided to bring in slaves from Africa to do the heavy work. The large-scale supply of European contract workers, African slaves and finally Asian contractors made the creation of what would come to be referred to as the “New World” possible.

Between 1492, the year Columbus set foot in the Caribbean, and 1866, when the last shipment of slaves was delivered to Cuba, about 10 million Africans had forcibly been transported to this so-called New World. An equally large number probably did not survive the preliminary stage of sourcing slaves — the slave hunts in Africa and the crossing.

Many of the African slaves being transported like packed sardines in ships were beaten or starved to death, some committed suicide, and lots more were raped and killed and then thrown overboard.

The British, French, and Portuguese were the main slave traders. However, the Dutch share in the slave trade was about 5%. Out of this half a million “Dutch” slaves, about 275,000 Africans ended up in Suriname. Slaves were also brought to the Antilles, and were mainly put to work in the salt pans.

The Dutch in Suriname

In the more than fifteen years that the British had been in Suriname, they had already built up two hundred sugar plantations. These were taken over and expanded by the Dutch. Plantation entrepreneurs were given plots of land to cultivate where initially, sugar cane was mainly grown, and later, coffee, cotton, and cocoa would also be cultivated.

In that same period, plantations with romantic names such as Mon Désir, Roosenburg, and Goede Vrede started to spring up, especially on the coast and along the rivers.

In the eighteenth century, the Surinamese plantations were an extremely lucrative enterprise; between 1680 and 1780 the number grew from 200 to 591. Later, partly due to the mismanagement of the often absent owners, they stopped making profit and their numbers also decreased.

However, the Dutch economy continued to benefit greatly from this tropical appendage. In his book “Surinaams Contrast,” Alex van Stipriaan, professor of South American history at the Erasmus University in Rotterdam and curator at the Royal Tropical Institute, calculated and stated that the export of products from the plantations between 1750 and 1863 yielded at least 600 million guilders!

Further benefits for the Dutch

The Netherlands’ trade monopoly on Suriname also resulted in an economic spin-off in the Netherlands. Van Stipriaan said: “All supplies for the plantations, from nails to bricks, had to be delivered and transported from the Netherlands. The dozens of ships that sailed up and down every year between the Netherlands and Suriname provided the shipyards with considerable work and employment.”

This basically meant that while the Netherlands enjoyed considerable returns from slavery and the plantations in the Caribbean colonies, back home they also enjoyed a high level of employment creation from producing all the materials that were needed for the sourcing and transportation of slaves, as well as the daily running of the plantations.

Think of the building of slave ships, manufacturing of all manner of chains and locks for the slaves, whips, and other cruel devices for their punishment, as well as tools for the tilling of the soil, planting and harvesting of crops, and other instruments for working on the plantations. All of these had to be produced and, in doing so, provided employment in the Netherlands.

All of this coupled with the free labour provided by the slaves helped build what the Netherlands is today.

Inhumane and cruel workload

As mentioned before, a lot of the plantations had romantic names like Mon Désir, Roosenburg, and Goede Vrede, where the daily harsh realities of plantation life were hidden. These plantations were nothing but homes to misery, cruelty, the most inhumane practices known to man, and places of torture where slave owners were free to inflict unimaginable pain and suffering on and kill their slaves in whatever ways they liked.

The plantations also had a high mortality rate. The tropical climate, in which infectious diseases thrive, was one of the main causes, as well as the hard and inhumane workload. In the initial expansion phase of colonisation, when the swampy Surinamese coastal plains had to be tilled and reclaimed, the whip was used to hasten the digging of ditches in the heavy clay.

The centuries-old oral traditions of the Maroons tell that the excavation work and the harsh and inhumane treatment by the plantation owners were important motives for them to run away. Due to the heavy rainy periods, even after the construction of the plantations, it was important that the waterworks and the drainage system were well maintained and regularly dredged.

In addition, the daily work on the plantations also had to go on. The slaves worked six days a week and often at night. They were only given a few days off around New Year’s Eve. Working on the sugar cane plantations also came with its own risks. It often happened that a slave would injure themselves while cutting thatch.

Dispensable labour

In cases where treating an injured slave would cost the slave master a lot of money, they would either abandon the slave to die or shoot them dead. There were also cases of injured slaves who were “beyond saving” being taken into the jungle and hunted for fun by their masters and friends. A form of leisure time hunting but with a human being as prey.

Working in the mill or the cookhouse was even more dangerous. Slaves regularly landed on the wheel of the mill or fell into the kettles in which the sugar was boiled. And this was mainly the reason why sending slaves to work there was a form of punishment. The hygienic conditions were also terrible. Many slaves died of lung diseases, schistosomiasis, and dysentery from working in dusty sheds and drinking polluted water.

Moveable property

Until 1828, slaves were not regarded by law as human beings or people, but as (moveable) property. They did not have any civil rights and, in principle, were not allowed to own property. They could also not legally marry amongst themselves, and being married to a white person was seen as taboo and against the law.

Victims of the slave trade would later legally be recognized as human beings in 1828. However, they would be classified as “infants,” over whom their owners had to exercise “paternal discipline.”

The slavery archives of the Netherlands contain numerous inventories of plantations, which contain a description of fields, buildings, and livestock as well as the lists of slaves. In addition to their names and functions, it also mentions the condition of the slaves.

Their value was often determined on the basis of all of this. The inventory of the Roosenburg sugar plantation shows, for example, that Trobel, “Chief carpenter,” was valued at 1500 guilders. Vorte Jacoba, “Field maid,” was worth 325 guilders. The elderly, children and handicapped people often didn’t yield much.

“Inferior creatures”

On average, a slave was worth about 340 guilders. In correspondence between Surinamese administrators and investors or interested parties, there were often constant complaints about the high mortality rate among the slaves. “This invariably resulted in requests for funds to purchase new slaves. These administrators hardly ever asked for permission to spend more on the care of the slaves,” says Van Stipriaan.

As a reply to the prohibition of slavery and slave trade by the English, the Dutch government drew up some regulations for slave owners to try and get them to treat their slaves somewhat “better”. In the Netherlands, few people protested against slavery or the ill-treatment of slaves. Those who did still considered them inferior beings.

It was not until 1842 that the movement for the abolition of slavery, which had become widespread in England, inspired supporters of the Protestantse Réveilbeweging (Protestant Réveil movement) to found the Society for the Promotion of the Abolition of Slavery.

Origins of colourism and the one-drop rule

Initially, the plantation owners used corporal punishment mainly to terrify the slaves, who outnumbered them. They feared uprisings, and to discourage it, they often looked for ways to psychologically subdue and shackle the slaves. A notorious punishment was one in which the victim was wrapped around a stick in the ground, after which they were beaten with a bunch of twigs until there was no more flesh on their buttocks.

Sometimes a slave’s legs were tied to a tree, and the soles of their feet were moistened with saltwater. A tethered and thirsty goat would then lick their feet until the flesh was worn away.

Another way that slaves were oppressed and “kept in line” was to play them against each other. Light-skinned slaves (Mulattoes) were always favoured over “black” or dark-skinned ones. They did not have to do fieldwork and received larger food rations. They were told that if they kept an eye out for the masters, they would be rewarded. Light-skinned slaves were often the products of interracial relationships, mostly as a result of black female slaves being raped by their white masters.

However, even though these light-skinned slaves were more favoured than the dark-skinned ones, they were still seen as “tainted” people. The white populace and their slave masters saw them as a case of “white blood being polluted by black blood.” And as a result of this thinking, they were never considered white. This is the origin of colourism and the “one-drop rule”.

“The one-drop rule is a social and legal principle of racial classification that was historically prominent in the United States in the 20th century. It asserted that any person with even one ancestor of black ancestry (‘one drop’ of black blood) is considered black (Negro or coloured in historical terms).”

Although the whip never completely disappeared, in the nineteenth-century attempts were made to bind slaves more to the interests of the plantation by improving their material conditions and converting them to Christianity.

The Christian faith used to be taboo for slaves, because, as the slave masters often put it: “De Hemel was voor geene Swarten gemaakt, die waaren alle des Duyvels, die moesten maar werken en de planters tot playsier zyn.”

“Heaven was not made for blacks, those are just devils, that must work and be obedient to their masters and plantation owners.“

Segregated plantations

Furthermore, white and black inhabitants of the plantations were strictly separated, although the white men liked to make an exception to that rule when it came to raping slaves. As a result of this separation, the slaves developed their own religion and their own language, Sranantongo — a combination of English, Portuguese, and other African tribal languages.

The plantation owners had a poor command of this language and therefore often did not realize that the songs (Negro Spirituals) the slaves sang had a critical undertone. Due to the slaves managing to develop their own culture, they became more independent and gradually dared to make more demands, for example with regard to working conditions.

Protests

In the course of the nineteenth century, there were also group protests, for example when slaves were forced to move to another plantation. They had become “attached” to the plantations where they were born and where their ancestors were buried and did not want to be separated from their families. Slaves who worked on a coffee or cotton plantation also preferred not to exchange them for a place on a sugar plantation.

Sometimes these protests were successful, but in most cases, the slaves were either punished or killed to set an example. They also openly protested when acquired rights, such as days off, were compromised. This of course doesn’t mean that there were no initial slave resistance or uprisings, it’s just that the nature of the resistance changed over the years.

The Maroons

At the beginning and initial stages of slavery, some of the captured and transported peoples managed to escape. Slaves who escaped and tried to survive in groups in the jungle were called Maroons. Famous Maroon leaders such as Boni, Baron, and Joli Coeur caused a lot of panic among plantation owners in the second half of the eighteenth century.

They regularly carried out armed raids on plantations to liberate others and to steal supplies and weapons. They waged a sort of guerrilla war against slave owners which affected business so much that a treaty had to be drawn up.

For most male slaves in the plantations, military service was also a path to freedom. The Redi Musu, or the red hats, were slaves who fought for the colonial government and plantation owners. They were made to fight against slaves who escaped the plantations and revolted. And contrary to popular belief, they did not volunteer to fight for their white masters. They were forced to.

Why is the Dutch slavery history not a major topic in the Netherlands?

It is quite remarkable that not a lot of people in Dutch politics and the halls of government talk about the Dutch colonial/slavery history, and the attempts that white people often make to kill the conversations surrounding the topic because of how uncomfortable (white fragility) it makes them.

Up until now, Dutch colonial/slavery history has had no place in our collective memory, it cannot be found in our national history, or in our education, and is not even “worthy” of being commemorated as a nation. Our leaders and those in government continue to choose to have a “difficult relationship” with the truth about the dark sides of our national history.

READ MORE | Dutch Slavery: Our Dark Past

This difficult relationship also extends to the structural violence used by the Dutch army during the Indonesian War of Independence. Nobody talks about these things and somehow, we are all expected to just forget about these past events and move on.

The fact that discussions on the Dutch slavery past are now being had in government, and Emancipation Day is also now commemorated annually, is certainly not due to a general attitude by the Netherlands to willingly face her dark past.

It is mainly the result of the admirable and relentless efforts of the Surinamese, Antillean, and African communities working in unison with both white, black, and colored historians, activists, and others fighting racism, and also calling for the recognition of what their ancestors suffered at the hands of the colonizers and slave owners.

A similar story: Asian colonies

The same silence is applied to the Dutch slave history in its former Asian colonies. The Dutch government abolished slavery in these territories as late as 1860, followed by its American colonies in 1863. In practice, however, after 1860 slavery continued to exist for many years in the Indonesian archipelago, albeit on a reduced scale.

In the West, the slaves were brought from Africa. In the East, it was mostly the natives. The Surinamese and Antillean communities have much more awareness of a common slavery past.

The hundreds of thousands of Indo-Dutch and Indonesians in the Netherlands have little or no knowledge of and awareness of slavery in the Dutch East Indies. The many descendants of the slaves have disappeared imperceptibly into the common population.

READ MORE| What was the VOC? The Dutch East India Company explained

When it comes to the Dutch slavery past in the East Indies, there has never been a tenacious group of descendants who demand recognition of its history. Nor is it expected that such a group will arise, simply because the vast majority of the descendants of the enslaved in the East are unaware of their own history of slavery.

So should the Netherlands then continue failing to recognize and remember all these important parts of her slavery past? Should the government continue to ignore the importance and significance of Keti Koti? Why is commemoration important?

I think every Dutch person who observes minutes of silence on Remembrance Day on May 4 definitely understands why commemoration is important. May 4 commemorates all civilians and members of the armed forces of the Netherlands who have died in wars or peacekeeping missions since the beginning of WWII. It is also a day, among other things, that the young generation is made to learn and reflect on the events of WWII and understand how we must continue to make sure that they never happen again. Never forget and never again!

Keti Koti: paying respect to victims of slavery

Keti Koti isn’t just a celebration, and it’s not just about paying respect to victims of slavery and their (conscious) descendants, but is of course also intended to make sure that the horrible atrocities of the past are never forgotten; to become aware of our actions in the past and the present, to (continue to) look at them critically, to learn from them, and to do better in the future.

Moreover, it is a mistake to think that as a country, if we just keep on denying and ignoring our slavery past, the rest of the world will never know and it would all eventually go away. It’s equally sad and shameful that some politicians and their voters often refer to talking about this dark part of our history as “political correctness.” That is extremely false.

Rutte’s response

In 2020, during the Black Lives Matter marches and protests triggered by the murder of George Floyd an African-American man by American police, Mark Rutte, the prime minister finally came out to admit that institutionalized racism does exist in the Netherlands. A welcomed first step by a white tone-deaf politician who for many years has refused to admit that racism is a problem in this country and that Zwarte Piet is a racist tradition.

READ MORE| Does the Netherlands have a blind spot for racism?

Despite coming out to say that his attitude towards Zwarte Piet has undergone major changes, and kickstarting the important discussions about racism, slavery, etc, in parliament, marginalized communities still feel a deafening silence regarding their plights in this country. The tone-deafness from white politicians is an ever prevalent occurrence. The child benefits scandal that saw the dissolution of Mark Rutte’s cabinet can clearly bear testament to this fact.

Finally …

For centuries, the slavery history of the Netherlands has been covered up and hidden from posterity. It is therefore high time that not only our education about our slavery past is improved, but that white people, especially those in government and positions of power, put aside their white fragility and face the realities of the past atrocities committed by the Netherlands.

Ignoring this part of history will not make it go away. After all, ignorance of the Netherlands’ slavery past and the resulting false national self-image that is often fostered by an unconcerned government and white people constantly silencing the affected communities, is the root of intolerance, racism, and xenophobia in this country.

A nation that does not want to confront its past mistakes and realise that it had (and still has) an effect on the people that suffered (as well as their descendants), but would rather ignore one of the darkest parts of its history, is not only living in a fool’s paradise but also has no right to command any respect or moral authority on the international stage.

READ MORE| Zwarte Piet: the full guide to the Netherlands’ most controversial tradition

The more the Dutch government and the Netherlands refuse to acknowledge their slavery/colonial past, apologise for it, and seek to do better by the communities and descendants of those once enslaved, the more it will continue to reap the systemic discrimination of already marginalized groups, internal irritation, and profuse scorn.

In order to heal and focus on the future, we need to confront and own up to the mistakes of our past. Maybe the Netherlands and the Dutch government should take a leaf from Germany’s book. Observe how they talk and teach their young ones about their dark Nazi and Holocaust past. Being honest and open in talking about it definitely helps with making sure that white fragility is gradually made a thing of the past and that such atrocities never happen again in the future.

Slavery is so much more than just a dark page in the history of the Netherlands. It is the foundation on which this country’s wealth, growth, and development have been built. We would be lying to ourselves if we say that today, the Netherlands is still not enjoying the benefits of all those years of slavery and colonisation. The truth is, you cannot be involved in the slave trade, and do it for more than 200 years, and somehow expect that it wouldn’t have any effect or repercussion on your future.

The descendants of those who were forced to give blood, sweat, tears, effort, and their lives to build the foundation on which this country stands, are still here today. To recognise them is to respect their ancestors, and the Netherlands can start by making the discussion about slavery as open and honest as possible.

Amplify the voices of these communities. Let them speak and let those in power listen and learn. The Caribbean, Indo-Dutch, and Indonesian communities are part of this country. They deserve to be heard. It’s high time the Netherlands unveiled a “Memories and Truth” commission to look clearly at the wounds of the pasts and the consequent pains of today, as well as a slavery museum which would create a much-needed platform for the stories of slavery in the Dutch colonies to be told. Temporary exhibitions about slavery in “white museums” are not enough. Imagine what we would all learn if we gave these communities the proper platforms to speak and tell their ancestors’ stories. Imagine how much they can’t speak of because of fragile white people constantly shutting them down and derailing the conversation. A “Memories and Truth” commission would go a long way in giving them a safe platform to speak up and not just tell their stories but those of their ancestors.

Whether this initiative would ever become a reality is left to be seen. For now, we continue to commemorate Emancipation Day and remember those who were once enslaved and later succeeded in breaking their chains.

Did you know about this chapter in Dutch history? Let us know your thoughts in the comments below!

Feature Image: Willem van de Poll/Wikimedia Commons/Public Domain

A 2019 survey showed that the Dutch hugely overestimated the role of the Netherlands in the Atlantic slavetrade. They are taught about it in school but I guess many are just fed up with people projecting American history and racism on the Dutch. Try talking about Dutch history from an actual understanding first.

BTW, the WIC had the monopoly on the Transatlantic trade, so until the WIC got permission to capture Portugese slave forts and enter the slave trade, which was quite a big deal with strict conditions (free after 7 years and educated in christianity) which weren’t met, there was no Dutch slave trade. Dutch protestantism was opposed because it all people were god’s children, that’s why everybody in the Dutch Republic was free and the mostly male blacks in the Netherlands married white Dutch wives.

What ‘we’ as in Dutch people know is that it shows Dutch hypocrisy and the “Koopman en de dominee” goes back quite a while. There was a double standard for the world outside, the colonies. One of the perks of the triangular Transatlantic trade was that normal freight ships left Zeeland and normal frieght ships returned. It was at the African West-coast with our good African friends and partners in crime who sold the people they had enslaved where the ships were made into slaveships, to be restored to freight ships in the America’s before returning to the Dutch Republic. It wasn’t secret but less confrontational was better and slavery was still frowned upon, not something to boast about because the homeland Dutch didn’t share that British/American idea of inferiority and colorism.