Remember that time the Dutch government gave artist’s actual salaries in exchange for their work? No? Allow us to refresh your memory!

Are you an aspiring Dutch artist in the 70s rebelling against the system, using contemporary art to promote your progressive ideals, but struggling for a sustainable income? Fear not!

With the BKR (Beeldende Kunstenaars Regeling) — an artist subsidy scheme — you can hand over your artwork to the government and get a salary in return, so that you can keep fighting the very system that simultaneously provides you with food and shelter. I’m sure nothing would go wrong.

Jokes aside, we have to give credits where credit’s due. The BKR was a bold and unique social assistance that helped many artists after the Second World War, including famous artists like Armando, Jan Wolkers, and Marlene Dumas.

Learning from Fransje Kuyvenhoven’s research on the BKR, we can see that the scheme had a turbulent existence that garnered a rather negative public image which it may or may not deserved. From its birth in 1949, to its peak in popularity in the 70s, which subsequently led to its downfall in 1987, the history of the BKR is certainly worth remembering.

“Do not hand in wet”

When the BKR was first established in 1949, its goal was to help struggling artists on their way to financial independence. Dutch municipalities could implement the BKR voluntarily and set up commissions that valuated the worth of a submitted artwork.

The artwork would then be bought by the government and the price would be recalculated into a weekly salary for the artist. So far so good. But just like any welfare system that sounds a bit too good to be true, it’s bound to be abused by some folks.

The anecdote goes like this: a Rotterdam artist Rijn Rijnse (there’s possibly humor in his name that’s too Dutch for me to understand) walked into a bar one day and remembered that he needed to hand in an artwork for the BKR, so he threw some paint on a canvas and handed it in when it was still wet. That very afternoon he came back to the bar and declared with satisfaction that his “scribblings” would keep him fed for a few more months.

Such a stereotype of an artist living on BKR subsidy was very wide-spread across the Netherlands, so wide-spread in fact, that it’s rumored that an art collection point in Amsterdam once hung up a board with “Do not hand in wet” on it.

Research carried out in the 80s showed that 20% of the artists using the BKR were indeed exploiting the system. Unfortunately, the other 80% of honest workers might have still contributed to BKR’s eventual termination by, ironically, working too hard.

Drafty attics and damp basements

In 1969, the BKR experienced an explosive growth in members. Lured by its benefits, students flocked to art academies, foreign artists immigrated to the Netherlands, artists moved to the countryside to ask for membership, and with the help of the BKR, women felt that they could finally become the bread-winner.

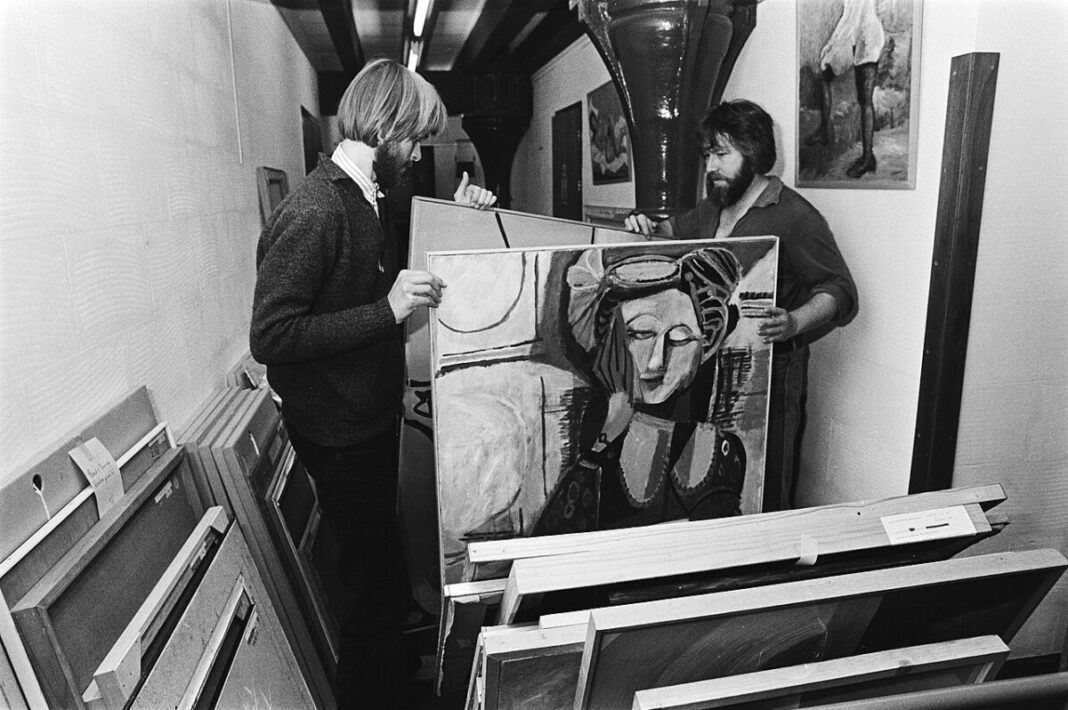

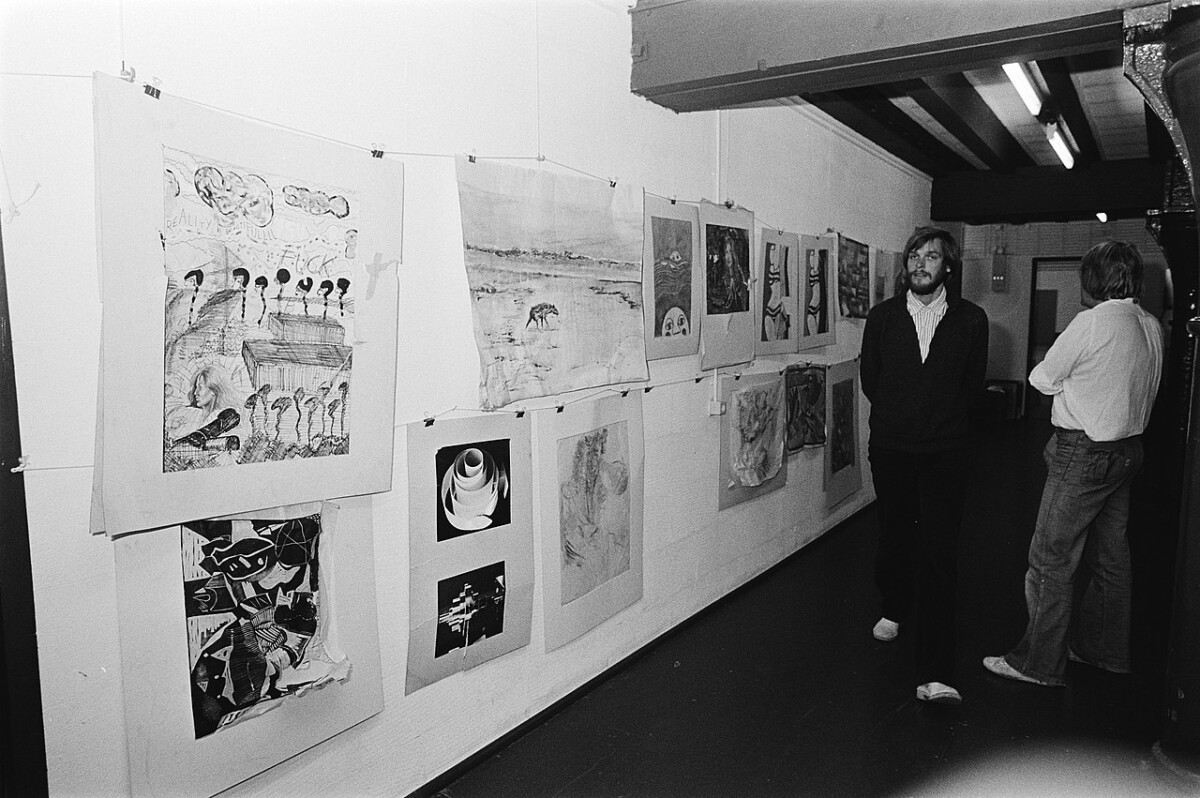

Municipalities were flooded with such a massive amount of artwork that many of them couldn’t find enough storage space to preserve them.

Before 1969, 75% of the BKR artworks were taken in by the Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands. Because the agency’s depots had run out of space by 1969, it took in only 50% of artworks from then on.

From 1978, the Cultural Heritage Agency tried its best to take in as few artworks as possible while renting out many works as fast as they could. The municipalities weren’t doing too good either. Stories of irreversibly damaged artworks in drafty attics and damp basements were picked up by the media, while the cost of both storage space and artist salaries piled up.

Thousands of artworks

Just to illustrate how many artworks there were, here are some facts. When the BKR was finally abolished, the Netherlands had half a million more artworks sitting in its warehouses.

READ MORE | Van Gogh’s hidden painting unveiled after a century of private ownership

Of these, 20,000 pieces were declared “museum worthy” and the rest were given the usual treatment of mediocre art. They became wall decorations, were given to institutions as gifts, returned to the artists, slowly trickled back into the market, or were simply cut up and made into relatively attractive notebook covers.

“Politicians go behind your back”

Shouldering huge financial burden, the Ministry of Social Affairs turned to tighter regulations and austerity measures, both of which were met with fierce protests. It was the beginning of the end.

The desperate artists, armed with rage-fueled creativity (the worst kind of creativity), were fighting a losing battle.

One good thing that came out of all these, is that some of the protests were arguably hilarious. Museums were occupied by hundreds of artists, including the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam (twice), the City Museum in Schiedam, the City Museum in Alkmaar, the Boymans van Beuningen and the City Museum in Groningen.

And by “occupy” I mean sleeping peacefully in front of paintings. It would soon be apparent that artists were much more respectful towards artworks than politicians.

In 1983, State Secretary for Social Affairs Louw de Graaf tried to explain the austerity plan and was met with multiple flying objects including paint, chairs and microphones. Prime Minister Lubbers Brinkman, on the other hand, got a pie in the face.

READ MORE |Dutch history: that time when the crowds ate the prime minister

Three years later, a group of artists set up 150 gallows in the open-air theater of the Zuiderpark in The Hague—one for each member of the House of Representatives, obviously. Another group expressed their displeasure with a painting titled “politicians go behind your back” that depicts Lubbers standing naked with a quirt in hand and the devil at his side.

Some would argue that the protesters might have shot themselves in the foot with these wacky antics. And they are probably right. Because columnists sure went to town with all the commotion. And we all know how persuasive media can be, especially when humor is involved.

The Republic of Rottum

When 35 artists traveled to Rottumeroog — an uninhabited island in the Wadden Sea — to proclaim it the “Republic of Rottum” in protest, a columnist of De Telegraaf was delighted by the idea of all 3163 visual artists living in harmony on a small island away from the Netherlands.

The only problem was, each artist would possess a total of one square meter of living area. The Republic of Rottum would’ve looked like a breeding ground for penguins.

End of an era

On January 1, 1987, the government finally pulled the plug on the BKR. It’s a shame that its legacy always has a negative connotation to it. After all, the BKR did its job, albeit a bit too well.

When Karel Appel passed away, nobody mentioned that his famous painting “Questioning Children” was sold through the BKR. Even Appel himself denied that he was ever a part of it. It would be a shame to forget the BKR’s history.

We might learn something from it, like never throw a pie in the Prime Minister’s face if he writes your check.

Had you heard about the BKR before? Let us know your thoughts on this retro initiative in the comments below!

Feature Image: Hans Van Dijk/Anefo/Wikimedia Commons/CC1.0