Despite the call by the WHO for “testing, testing, testing!” as a way of controlling the spread of coronavirus, the Netherlands has, due to shortages in tests, “given up” on checking the actual numbers of infected people, and opted to only test the most critical cases.

In fact, RIVM itself states that those numbers are not telling much anymore and that we should look at the numbers of patients admitted to the ICU as an indication of the transmission of coronavirus across the country. (BTW, if you want to know how many tests are performed and what percentage of those is positive per day, here’s the link: https://www.rivm.nl/coronavirus/covid-19/informatie-voor-professionals/virologische-dagstaten)

Northern provinces

Meanwhile, the northern provinces, Drenthe, Groningen, Friesland and Overijssel, are adopting a different policy: massive testing of healthcare workers and their relatives/housemates, in an effort to contain the spread of the virus within the hospitals, and extensive contact research of those who are positive (up until two days before they were symptomatic).

Dr. Alex Friedrich, head of the Medical Microbiology department at the UMC Groningen, explains that this is possible because the virus hasn’t yet spread so much in the north of the Netherlands: therefore the strategy of containment, as opposed to that of mitigation, still makes sense.

Other than the fact that the northern provinces are geographically distant from the corona epicenter in Brabant, they have also been (so far) partially spared from the epidemic because their holiday weeks came earlier, when northern Italy (a popular destination for Dutch holiday-goers) wasn’t yet so affected by the virus.

Testing, testing, testing

We have so far been told that the reason why test, test, test is not possible in the Netherlands is that the amount of tests is limited. How is this possible though, when a relatively poorer country such as Italy can conduct thousands of tests per day?

“When the virus had not yet arrived, it was said: there will soon be two test labs, at RIVM and Erasmus MC, and there will be twelve upscaling labs,” Dr. Friedrich explains. “In hindsight that was a bad choice because it resulted in an extremely strict policy for the eligibility for testing, and the test capacity was quickly exhausted.”

Comparing that to Italy and Germany, while there was no quick action at the beginning, testing is now a priority. “Now, in Italy, they can handle 100,000 and in Germany 160,000 tests per week. Adjusted per population, that would mean 33,000 tests per week for the Netherlands,” says Dr. Friedrich.

“In the north, we quickly said during a group conference: it doesn’t matter what RIVM says, we are going to prepare all labs. That’s five in total. If we look at the numbers, we are now testing three to four times more than the rest of the Netherlands, with fewer inhabitants.”

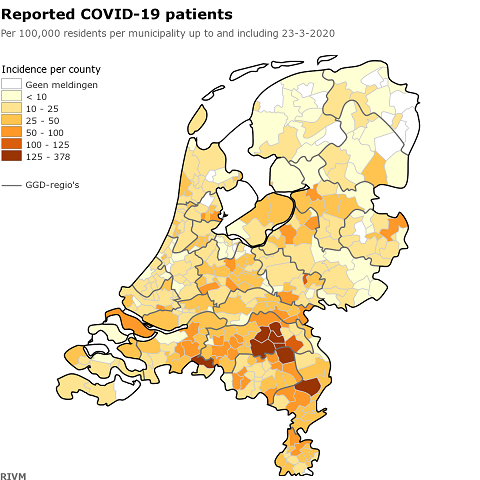

Subsequent corrections in the system may lead to changes.

The place of residence of 184 patients is still unknown. Image: RIVM

So how does he feel about the message that testing capacity is limited — and how can it be overcome?

“I never understood why this is always maintained. We don’t have a capacity problem. It is possible that a certain lab has a shortage of certain materials, but that is business as usual, you can solve that. This is not the case, as long as you are not dependent on a commercial party. We don’t need such a party either, because you can do these tests in almost any ordinary lab.”

A similar point is raised by Bert Niesters: “There are enough tests; you just need to have enough testing material, such as the plastic consumables. We have learned from previous epidemics that it is necessary to have a stock of them; that is why over the years we have accumulated a large stock of those plastics, and can afford to test more easily. Many laboratories depend on a single manufacturer. That is why testing is not possible in parts of the country. ”

The Netherlands has the highest number of medical microbiologists per capita in Europe, according to Dr. Friedrich, so it seems counter-intuitive that this does not give the Netherlands an advantage.

Dispute with Minister De Jonge

Such a ‘rogue’ approach from the northern provinces hasn’t been received enthusiastically by the health minister: his response was that every province should coordinate and follow the same guidelines.

“I understand what De Jonge wants to say” says Friedrich. “But we handle the tests very efficiently and do not use more than is determined by triage decision. We are however increasing capacity in case the next few weeks are needed”, he says. With the ‘triage decision’, Friedrich refers to the GGD’s assessment of whether a healthcare worker is eligible for a test – they must have had complaints for at least 48 hours.

Do you think the rest of the Netherlands should follow the northern provinces examples? Tell us your thoughts in the comments below!

Feature Image: DutchReview/Canva