Someone once asked me why Dutch folks never wear helmets when they’re on a bicycle, and after much deliberation and a long conversation about that, we came to the conclusion that when Odin created the Dutch, he created each and every one of them with a bicycle.

The Dutch are so obsessed with bicycles that they can ride them drunk, high, and even in a high-speed chase. Most Dutch folks even have more than one bike — one old and rusty one for running everyday errands, and another new and expensive one for outings, work, etc.

With 22 million bicycles for 17 million inhabitants, 32,000 kilometers of bicycle lanes, and the largest bicycle parking facilities in the world, the Netherlands could absolutely claim to be the world’s number one cycling country.

How did we get here?

The two-wheeler has become an indispensable means of transport in our country, and while the flat Dutch landscape may have something to do with it, one still has to ask how we came to be a cycling country in the first place.

The truth is that the Netherlands has not always been a cycling country. In the 19th century, Great Britain, Belgium, and Germany had more citizens with bicycles than we did. So how did the Netherlands become the country of bikes that it is today? Let’s take a historic trip down the Dutch bicycle lane.

Cycling in the 19th and 20th century

The first (velocipede) bicycles came to the Netherlands around 1820. Unfortunately, they weren’t a huge success, surviving mainly as an eccentric hobby for rich people.

Throughout most of the 19th century, cycling was mostly popular among the young and wealthy and was seen as a leisure time activity — mostly for daredevils. At the time, it wasn’t a means of transportation just yet.

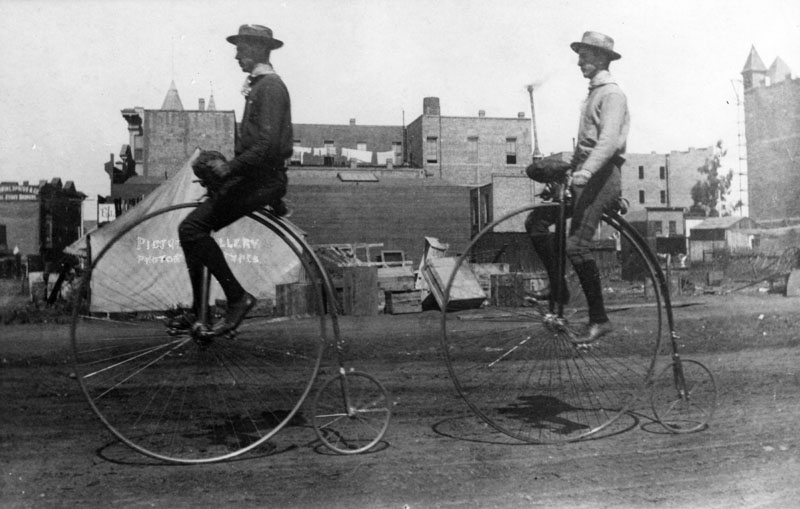

It was only when the penny-farthing (also known as high-wheel) bicycle came to the Netherlands in the 1870s that bicycles became more visible on the streets. However, compared to countries such as Great Britain, Belgium, and Germany, the bicycle was still relatively unpopular in the Netherlands at the end of the 19th century.

Bicycles for everyday transportation

It wasn’t until the Royal Dutch Touring Club (ANWB) — which was founded in 1883 by members of the velocipede clubs in The Hague and Haarlem — presented the bicycle in its advertisements as a means of transportation for everyday folks at the beginning of the 20th century, that its popularity really increased in the Netherlands.

That, in combination with its convenience and lower maintenance costs, gradually made cycling extremely popular in the country. Through years of multiple designs and development, bicycles started to look more like the ones we know today. No more velocipedes and penny-farthings, just the same size wheels and a lower saddle for comfortability.

What we know today in the Netherlands as the omafiets, or the “grandma bicycle,” came into being in 1901, but was called the Fongers Damesrijwiel at that time. This bicycle made it possible for cycling to become equally popular among Dutch women.

Who was Fongers?

Fongers was a company founded in Groningen in 1897. It pioneered the development of the classic Dutch touring bicycle and from 1884 manufactured a lot of high-quality bicycles, which, in the years leading to 1910, were only reserved for the wealthy.

As the years went by, their bicycles became more affordable. The company would go on to play a major role in making bicycles and cycling quite popular in the Netherlands.

In the 1920s and 1930s, the Netherlands began to make a name for itself as a cycling country and by the 1920s, there were already two million bicycles.

Cycling royals

In 1936, when the Dutch Princess Juliana and the German Prince Bernhard got engaged, they cycled on a tandem through the garden of Noordeinde Palace in a photoshoot which was their first appearance to the press as engaged royals.

Engaged royals cycling on a tandem — what could be more Dutch than that? To the outside world, the tandem which was used for the photo shoot would later give Princess Juliana the nickname “The Biking Queen” and just like that, the bicycle had made its entry into Dutch culture.

Blitzkrieg against bicycles: Nazi bike theft

Most people don’t realise how big of a role bicycles played during WWII. The Dutch Army (especially the Regiment Wielrijders), as well as German troops, made use of bicycles on a daily basis.

And here’s the interesting part: people desperately needed their bikes during the war. The bicycle remained one of the few possible means of transportation, as extreme scarcity of fuel made travelling by cars and buses virtually impossible for a long time. So Adolf Hitler ordered the confiscation of as many bicycles as possible because the Wehrmacht urgently needed vehicles to bring troops to the front.

This was pretty hard on the civilian population because the bicycle was the only means of transportation that most of them had. In some parts of the country, the populace was urged through pamphlets to hand in their bicycles, and those who didn’t obey had their bicycles taken from them by force.

After the war

Even shortly after the liberation, German soldiers stole bicycles en masse as they had to report to the Allies to be disarmed — and many chose to steal bicycles to get there. German soldiers in front of the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam were stopping protesting cyclists, pulling them from their bicycles and hastily riding off. About 100,000 Dutch bicycles were confiscated from the Dutch by the Germans with the help of Dutch collaborators, especially the NSB (the Dutch Nazi Party).

This confiscation of bicycles by the Germans was one of the reasons why there was a lot of bad blood between the Dutch and Germans for a very long time after WWII. The worst thing you could ever do to a Dutch person is to confiscate their bicycle.

In the first twenty years after the war, there were lots of references in Dutch media to the confiscation of bicycles by the Germans and all of them were an expression of anti-German sentiment. In subsequent years, things started to calm down and people from both countries could joke about it. However, the Germans truly came to realise just how much the Dutch love their bikes.

The bicycle or the car?

If you had to ask a Dutch person this question, there’s a very high chance that they would choose the bicycle every time. Despite the bicycle thefts by the Germans during WWII, the Dutch cycling culture of the 1920s and 1930s didn’t disappear. Most people didn’t own cars, and with fuel shortages continuing well after the war, cycling experienced a major revival.

In the 1950s, the popularity of cycling grew even further. So much so that in 1954, Amsterdam was allowed to host the first stage of the Tour de France, making it the first time that the race would be hosted outside of France.

Influx of cars to Europe

At the same time, the Marshall Plan was kicking off in the 1950s. With it, Europe saw an influx of countless American goods and services, one of them being American (made) cars. As European cities, industries, and infrastructure were rebuilt, more and more Dutch people could afford a car, and owning one was seen as a sign of wealth and prosperity. It was in this period that the bike faced serious competition.

The Marshall Plan

Also known as the European Recovery Program, the Marshall Plan was a US program in the 1950s aimed at providing aid to Western Europe following the devastation of WWII. It was a period where the US would provide more than $15 billion to help finance the rebuilding of Europe. The Marshall Plan was also meant to remove trade barriers between European countries and the US, as well as foster commerce.

With the car rising in popularity in the 1950s and 1960s, plans were developed by policymakers to radically change Dutch cities. The car was put in first place, new roads were constructed, and even the old Dutch city centers were redesigned to allow for the easy movement of cars. For the first time, the Dutch cycling culture faced a real threat.

Give us back our cycling country

Too much of anything isn’t good (unless said thing is a bicycle, then the Dutch are totally cool with it), so when it came to cars taking over their neighbourhoods, the Dutch didn’t like it. In the 1960s, in rapidly developing cities like Amsterdam, where so much focus was placed on giving cars free rein and the cities’ infrastructures were being redesigned to accommodate them, thousands took to the streets to protest.

The Jokinen Plan in Amsterdam saw thousands of Amsterdammers come out to protest against the city’s urbanisation plans, in which the general idea was to completely demolish overcrowded working-class neighborhoods such as De Pijp and the Kinkerbuurt, in order to make way for highways and high-rise buildings. These plans were ultimately halted.

The Singelgracht was also expected to be filled in and turned into a six-lane road. To this day, the plan is referred to as “the highway plan that almost destroyed Amsterdam,” and the locals are very proud that it was never implemented.

Furthermore, to protest against and stop the construction of a dual carriageway over Nieuwmarkt, 30 demonstrators bought a building that was on the route of the planned road, so that the municipality could not demolish the building, and as a result, could not construct the dual carriageway.

There were many more plans like the Jokinen Plan and all of them triggered so many protests at the time that even involved celebrities. The protests were all successful and large-scale motorways were banned from Amsterdam.

Protecting cyclists

At the same time, the hazards of owning a car became increasingly clear. In 1971 alone, 3,200 people died in Dutch traffic, 400 of whom were children under the age of 14. The Stop de Kindermoord foundation was established with the aim of guaranteeing the safety of young road users.

The foundation was very active in many ways, some of which were advising locals who wanted to tackle traffic problems in their neighbourhood and organising the Nationale Straatspeeldag with local groups — a special day where streets were closed to cars so that children could play safely. Politicians were also regularly approached by the foundation and asked to push through better policies in parliament. Through their protests and initiatives, change gradually started to come. It had finally dawned on the Dutch that the cyclist had to be put in first place and protected.

Environmentally friendly alternative

In 1975, the ENWB (Eerste Enige Echte Nederlandse Wielrijdersbond) was founded. The ENWB — nowadays called the Fietsersbond — was founded out of criticism of the ANWB, which according to the founders of the ENWB had become a lobby for car owners and car traffic.

The ENWB also proclaimed the bicycle as the environmentally friendly alternative to the car, and since the ANWB seemed not to care about the environment, the ENWB positioned itself as the environmentally friendly organisation with a lot of its members being conscious of the impact of driving on the climate. This was shortly after the oil crisis of 1973, with car-free Sundays being the first time the Dutch started to learn about the impact of cars on the environment.

Rethinking city design

In the early 1970s, policymakers began to concern themselves with citizens’ wishes to cycle more. Cycling had become a way of life, and since they couldn’t change that, they had to find ways to make cities bicycle friendly.

This led to policymakers rethinking the design of Dutch cities. For example, grocery stores, shopping malls, cinemas, and schools all had to be within cycling distance of residential areas.

As a result, people didn’t have to take the car to do groceries or meet with friends in shopping malls outside the city. The easy accessibility of public transport (bus, tram, and metro) stops by bicycle also made it easier to move around without a car.

The Dutch could quickly cycle from their houses to bus, tram, or metro stops (or train stations) and then take the train, tram, metro, or bus from there. Most things needed by everyday folks remained nearby, making it accessible by bicycle, and gradually, the country slid into its role as one of Europe’s most cycling nations.

More bicycle lanes

While the Dutch had done a lot over the years to show how much they loved their bicycles, one important ingredient of a cycling country that was still missing was an extensive network of bicycle lanes. In September 1885, the first bicycle lane in the Netherlands was opened on the Maliebaan in Utrecht.

The second bicycle lane would not be built until 1896. However gradually, more and more bicycle lanes came to be built even though the main reason they were constructed was to free the highways of the “annoying” cyclist.

In 1965, just under 7,000 kilometers of bicycle lanes had been constructed in the Netherlands, mostly on private initiative. In the 1970s, a number of bicycle-safe intersections and traffic lights had already been built in Leiden, The Hague, and Tilburg. Due to the increasing popularity of the bicycle in the 1980s, the government started to realise that more bicycle lanes needed to be built.

From 1978 to 1988, the Dutch bicycle network grew by 73% — from 9,300 kilometers to 16,100 kilometers — compared to an 11% growth of the motorway network. And since then, the bicycle lane network in the Netherlands has doubled, with about 32,000 kilometers of bicycle lanes today.

Emergence of the car-free city

While the 1960s saw plans to make way for highways, such as in the case of the Singelgracht in Amsterdam, the 1990s saw Dutch city centers increasingly being designed for bicycle and pedestrian traffic.

Fortunately, this development has continued to this day. With low-traffic and car-free zones, more and more cars are being banned from (large) city centers in order to improve air quality and make cities more environmentally friendly and attractive.

Furthermore, locals prefer seeing the medieval alleys around their old churches and canal buildings completely car-free. At the same time, the popularity of the e-bike, which makes cycling attractive for seniors, has significantly increased. E-bikes can also travel long distances, and most people who have them see no reason to own cars.

Cycling today

In a battle between cars and bicycles, bicycles will always win in the Netherlands. According to a 2018 study, bicycles in the Netherlands cover 13.3 billion kilometers annually. There are people who believe that maybe, one of the reasons why the Netherlands never succeeded in having established car brands like the French, Germans, and Swedish is because they’ve come to love their two-wheelers so much.

Today, the Netherlands has tons of different types of bicycles. There’s the cargo bike, recumbent bike, children’s bike, foldable bike… Children use them as a means of transportation to school, parents use them to take their kids to football and hockey practice, and others use them for various kinds of errands. Some (old) people even cycle all around the country (or Europe) during the summer vacation. To the Dutch, cycling isn’t just a necessity, it is also a leisure time activity.

As the Netherlands aims to be climate-neutral by 2050 — achieving an economy with net-zero greenhouse gas emissions — the government will need the populace to cycle much more than ever before.

The bicycle has cemented its place in the Dutch transport culture and I’m afraid it’s not possible to be Dutch without being a badass on a bicycle. Who would have thought that something that once started as a leisure time activity for the rich would go on to become a mode of transportation that is both cheap and environmentally friendly?

How do you feel about cycling in the Netherlands? Are you as crazy about bikes as the Dutch are? Let us know in the comments below!

Feature Image: Berke Halman/Unsplash

A fantastic article! THX!

You’re very welcome! 🙂

I brought my DaHon folder from the USA on my first visits to NL. It drew an audience every time I set it up. With swarms of bikes everywhere my little folder still attracted attention whereas in the US it got no notice. Bringing my bike all the way from the US probably helped me fit in. I just knew I needed a bike to enjoy the trip. It’s like fietsen has gotten into our DNA.

Nice article promoting our national pride. I miss the reference to the Nationaal Fietsmuseum Velorama in Nijmegen where also Queen Juliana’s bike is and all the other bikes you refer too. The history is visible there for your readers.

i am a Dutchie living in Australia and i miss riding my bike, but would not dare to ride a bike here.

I recently had a Boat Bike tour in Holland which was a superb experience.

I enjoyed it all so much & would highly recommend the concept

Hello, I recently visited Holland and cycled from Europort, Rotterdam to Amsterdam to Almkerk and back to Europort.

Visiting Holland and cycling was a BIG mistake. I now realise just how bad the UK’s roads, cycle routes and attitude to cycling is.

It took a while to get used to being an equal on the rods and drivers giving way to me.

For whatever the reasons you Dutch came to such a great attitude and acceptance of cycling it is an amazing place to visit and cycle.