Dutch communication, eh? Now, I know what you are thinking. As the infamous stereotype goes, just go into every conversation like a bull in a china shop and say whatever you want, as bluntly and direct as possible. If people are offended – helaas pindakaas, that is their problem. Well, yes. But ask yourself this: why is it so often deemed an acceptable approach here?

Intrigued? You should be.

By the end of this article, you will not just have a clearer idea of effective communication with Nederlanders, but also all cross-cultural communication. We’ll be delving into communication styles across cultures. Also, why some countries have entirely different approaches to communication — and how that can create problems.

Culture, culture, culture

Firstly, let’s look at you (yes, you). You have, largely, been nurtured in harmony with the culture and behaviours of the country that you grew up in, or have had the most exposure to. The way that we think, approach tasks, and what we find logical and acceptable, are all biases from our most familiar culture.

Yes, personalised events also shape us. Then there is Nature vs. Nurture, but there are characteristics shared through similar ethnicities, languages, histories, and religions. A decent first step before trying to understand and work with Dutch culture is to acknowledge and explore your own, as often we are not even aware of the depth of these influences. But how can that be done?

Low-context vs. high-context cultures

Cultures are incredibly complex so it’s not so black and white. There is certainly more than simply exploring low-context and high-context cultural theory. However, it’s a good place to start.

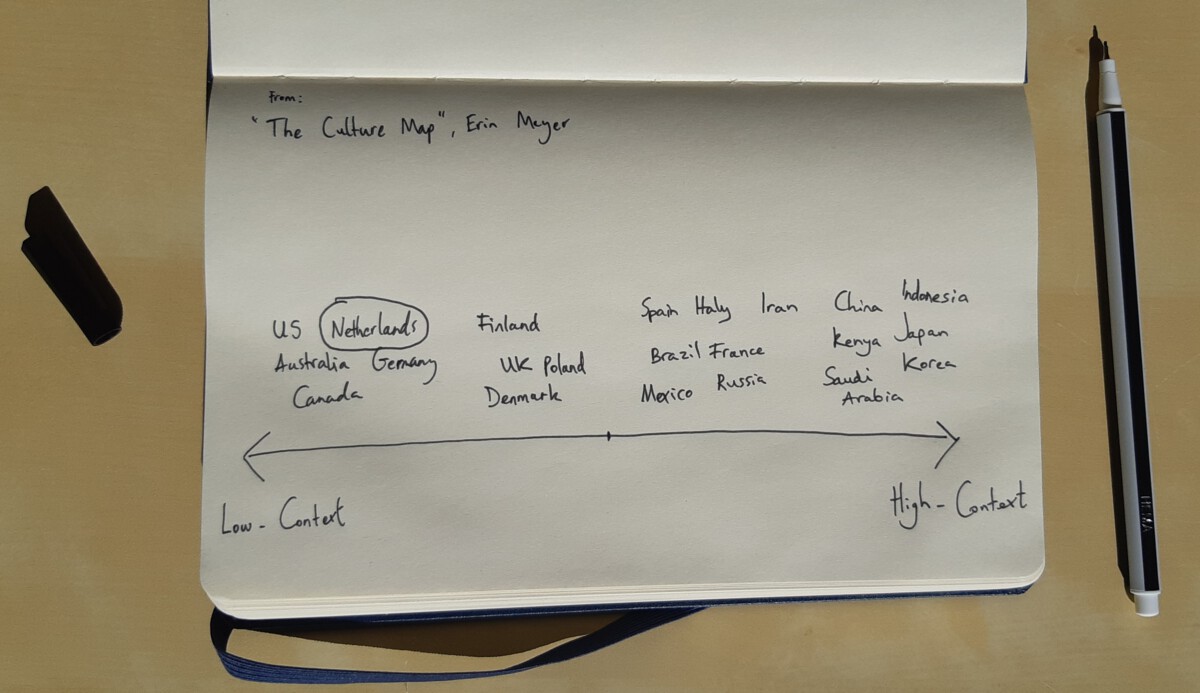

General patterns and characteristics are present in cultures which help us put them on a scale, such as this one (an example borrowed from Erin Meyer):

However, Meyer cautions not to get too obsessed with it. “What matters is not so much the absolute positioning of a person’s culture on a particular scale, but rather their relative positioning in comparison to you.”

So with that in mind, what are the basic differences between the two groups in terms of communication?

High-context communication traits

Information is shared implicitly, where context is king. It’s often indirect (read between the lines), extensive, and communication is considered an art. Non-verbal cues are key, such as voice tone, gestures, facial expressions, and eye movement. Disagreement and conflict are often seen as personal.

Low-context communication traits

Information is shared explicitly, with much less importance placed upon non-verbal elements. Communication is seen as a way of exchanging ideas, information, and opinions. So, the choice of words, conciseness, and clarity is of utmost importance to do that effectively. Additionally, repetition for the sake of good communication is acceptable. Disagreement is often depersonalised, with a focus on a “rational” solution to solve a conflict.

Ok, but what does this mean in practice?

Again, Meyer nails it. “If you’re from a low-context culture, you may perceive a high-context communicator as secretive, lacking transparency, or unable to communicate effectively,” she writes.

“If you’re from a high-context culture, you might perceive a low-context communicator as inappropriately stating the obvious…or even as condescending and patronising.’’

Interestingly, and probably to the amusement of low-context cultures, the two groups most likely to suffer from miscommunication are two high-context cultures. Their implicit interaction is based upon their own cultural nuances and behaviours.

The Netherlands, obviously, has as a (very) low-context culture. So next time you are at work with Dutch colleagues or with Dutch friends and neighbours, ask yourself this:

Am I communicating implicitly or explicitly?

If the answer is the former then good luck. You can be fluent in Dutch, a die-hard Ajax fan, and somehow convince yourself that stamppot is enjoyable and not bland, but that may not. be enough. If you’re still communicating with high-context culture mannerisms you will forever fall short of Dutch expectations.

READ MORE | We asked readers about their experiences with the infamous Dutch directness

The tip of the iceberg

Differences in communication is honestly just the start, and it’s a fascinating topic which is immensely helpful in a multi-cultural environment.

For example, attitudes to personal space and privacy; relationships; hierarchy and company structures; the approach and execution of tasks; the perception and importance of time; and learning are all aspects that can vary. These all depend on where your culture sits on the low-context to high-context culture scale.

So if you not only want to survive but thrive in the Netherlands, put some time aside to learn about low-context cultures. This isn’t to say that there is a golden standard for communication and behaviour, or that your own culture is incorrect so you need to change, just that it’s important to acknowledge and be aware of these differences to increase adaptability and efficacy.

It may just save you from a lot of future miscommunication.

Have you found it difficult to communicate in the Netherlands? Tell us your story in the comments below!

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in April 2020, and was fully updated in May 2021 for your reading pleasure.

Feature Image: Moose Photos/Pexels

I’m Canadian born with Dutch parents. I learned the language, went to school in Den Haag for 3 months at a time aged 6 and 12. I’ve also learned to ask tourist questions in English. When asked in Dutch, I’d get a look of disdain. “Waarom weet je dat niet?” Like I’m an idiot. Growing up in Canada we always apologize for everything. I love the NL people for their directness. My family there speaks BLUNT! 😝

i love Canada, i have lived 20 years there, and the tactful and respect to each other is highly appreciated, Here i found that the respect to each other is not a value, just to be direct, not matter how harsh and hurtful can be to the other

James, I would put Canada on the list under “High Context”: Canadians’ politeness gets in the way of clearly getting across what they mean, what they want, what they want from you. (From my personal, Dutch immigrant to Canada, perspective…

Overall, good read for a reminder. I wonder however how James Bogue has positioned Korea in his hand drawing, as Erin did not put Korea in her original map as far as I know. As a Korean who have been grown over 30 years in own culture, then worked in US for 4 years and now in the NL for 16 years in always international enveronment and company, although Erin’s points have some valid & interesting points to start with, still it is a bit rough generlization based on personal case studies and experiences. And Korean, Japanes or Chinese would not agree to place each of our stands on decision making and authority in close proximity.