Pillarisation (verzuiling in Dutch) is one of the most distinctive — and fascinating — characteristics of Dutch history and society. Yet, it’s not very well known by foreigners.

The idea behind it is quite simple: Dutch society is divided into pillars, and each is characterised by a unique system of political and social organisation.

Ultimately, a pillar fuses people together around a shared ideology and common values.

Instead of relating to their fellow Dutch countrymen, Dutchies end up identifying themselves with their pillar.

Does this sound confusing? Don’t worry — we’ll explain it more below!

The history of pillarisation

Let’s go back to the end of the 19th century when the division between the different religions in the Netherlands led to the development of pillarisation.

Catholics, conservative Calvinists, and the (non-religious) socialist and working class, in particular, rivalled to preserve their unique identities and values.

They began to create their own social and political institutions, forming a number of parallel societies that lived next to — but with their backs turned — one another.

This division into pillars was also a way for the elites to resist modernisation and secularisation, and to maintain control over the population for as long as possible.

The entire society was divided, with each pillar having its own institutions: schools, hospitals, shops, political parties, media — you name it!

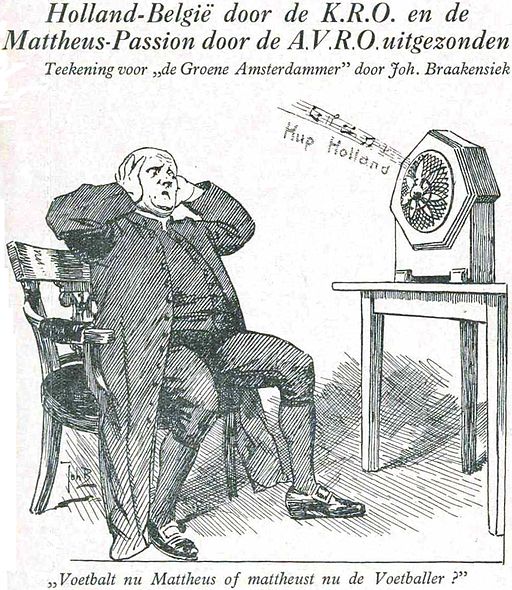

The role of media

Having their own media was particularly important. Through their own broadcasting companies, it was very easy for the elites to disseminate a cultural identity that people could then reproduce.

Consequently, Dutch society was completely divided into different groups. People from one pillar rarely mixed with people from another — they didn’t really have to!

It wasn’t only socially unacceptable, but doing so could be strictly forbidden.

As with most things, pillarisation in the Netherlands wasn’t black and white.

There was an overlap between the different pillars. For example, many members of the working class were both political socialists and practising Christians.

Some strict Calvinists, however, live in separate communities until this very day. Check out our article on the Dutch Bible Belt.

Societal changes shake up the pillars

Even though it lasted for some decades, the pillars started to break down in the 1960s.

Firstly, the economic growth of this period allowed the development of the Dutch welfare state, meaning that people didn’t rely as much on their pillar members.

Medicine, money, and support were now controlled by higher levels of governmental organisation rather than being provided by people’s immediate community.

The welfare state also allowed more Dutchies to access higher education and to own television sets — in these ways, people no longer relied on their pillar to know what was happening in the world.

Secondly, the pillars started to fall around this time because of the free spirit of the 60s.

As you can imagine, the peace-and-love mantra didn’t match well with people telling you how to behave and who to interact with.

The effects of pillarisation on freedom of expression

Before this time, the identification with a pillar was so strong that it altered the freedom of expression.

In the pillared society of the Netherlands, freedom of speech was effectively limited because you were supposed to follow the rules and values of the pillar to which you belonged.

READ MORE |Dutch Quirk #87: Invest way too much in window decorations to announce a new baby

The elites told you not only how to behave but also what to do if you wanted to belong to the group and reap its benefits.

Yes, the social control in the pillared system was extremely strong, but you couldn’t just leave it behind — unless you like to be completely on your own.

Today, it seems crazy to think that this was happening in the Netherlands, famous for its tolerant and forward-thinking culture.

Pillarisation nowadays

To all the future internationals in the Netherlands: breathe in, breathe out. The pillars indeed broke down, and the Dutch society was no longer pillared.

If you pay attention, however, you can still see some remains of it today.

Take, for example, the big, curtainless windows the Dutch have. You can easily see inside people’s homes. This is something that new internationals often find very strange.

READ MORE | Why don’t the Dutch like to use curtains?

But why do they do it? Because of pillarisation! With the very strong social control, one had nothing to hide, and the idea was that people could even check that.

It makes more sense now, doesn’t it?

Have you heard of pillarisation before? Tell us in the comments below!

Since taxes were paid according to the wideness of the houses: the broader your front was, the more tax you paid in the old days, typical Dutch Houses were build small, but very deep.

But when your house is deep and has a small front, you need large windows in order to have daylight in the middle of your house, if not it would feel as if you’d be living in a cave.

This is the real reason why the windows are that large.

The matter of pillarization on itself is true, but the large window-story is more of a romantization in that respect. The traditional houses were build way before the pillarization was that big of a phenomenon.

This is stupid.. We have large windows so more sunlight can come in the house. These houses are called ‘doorzonwoningen’. And looking in houses / living rooms is not considered rude, as long as you don’t stare to long/openly.

In fact we have decorations in the windows for people walking by to look at.

Narrow buildings and extremely narrow stairwells also meant furniture went in through the windows. A lot of the old buildings still have the posts the pulleys were affixed to. I don’t know how often that still needs to occur, as my time there was all in student housing, but I climbed many a stairwell I would not have wanted to carry even a twin mattress upwards within. And verzuilling was more than a little bit observable while I was there, although not so cutthroat as this seems to suggest.

My understanding is that WWII was a big driver of the breakdown of pillarization. For example, the resistance movement brought together catholics, calvinists, socialists, liberals, etc., fighting a common enemy, or they were forced to go underground (like my father) rather than get conscripted to go to Germany to work, and stayed with someone not in their pillar. Through this, the various groups found out the ‘other groups’ were good, normal people. As a result, the pillars didn’t make sense any more for the rank and file, despite the efforts by the leaders to return to the pre-war social fabric.