A lot of the time, it’s not entirely clear what the Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie (VOC) was, what it did, and whether we should be proud or ashamed of it.

The VOC (Dutch East India Company) is crucial to Dutch history. If you’ve lived in the Netherlands for a while, chances are you’ll have heard of it.

Let’s take a deep dive into the world of the VOC. For over 200 years, the VOC brought the Netherlands international power and wealth while exploiting local populations, creating colonies, and trading in human beings.

READ MORE | Dutch history hacked: 2500 years of Dutch life in 7 minutes (VIDEO INSIDE)

The story of the VOC is complicated, and this is not an exhaustive history of it (if you want that, there are plenty of books to choose from). This article offers a primer on the VOC: a less-than-casual introduction. Enjoy!

How did the VOC begin?

The VOC was established in 1602 with the goal to trade with Mughal India, where most of Europe’s cotton and silk originated. Quickly, the Dutch government gave it a 21-year monopoly on the spice trade with South Asian countries, and the company took off from there.

READ MORE | Myths about Dutch history and the truth behind them

Sounds nice and simple, but the VOC soon became the first conglomerate company: a fancy way of saying they did many different things (like shipbuilding, slave trading, and colonisation) under the same company name.

What was the VOC?

In the early 1600s, the VOC became the first company listed on the stock exchange. Along with its worldwide reach and transnational employees, this is among the reasons the VOC was a forerunner of modern-day multinational corporations.

The VOC had powers that a corporation today would (hopefully) never have: it could wage war, take and execute prisoners, coin money, negotiate treaties, and establish colonies. And so it did.

As much as modern-day corporations like Google and Shell have way too much power, the VOC was on a whole different, scary level.

Where did the VOC operate?

The VOC started operating in India and South Asia in general. Over the next century, it expanded its operations to Mauritius, South Africa, Indonesia, Taiwan, Japan, Malaysia, Thailand, and Vietnam.

Not all of these locations were the sites of permanent settlements or even permanent trading posts: but listing them all here gives us an indea of how massive this company was.

READ MORE | Tale as old as time: the Netherlands and India’s surprising relationship

How did such a transnational company work in the age before instant communication? It was, in fact, far more than a company — it was also a war machine.

What was happening in the Netherlands when the VOC was in operation?

The VOC was ostensibly founded after a Dutch ship returned from South East Asia filled with very profitable spices in 1596. What was going on in the Netherlands that would have made this massive company worth investing in?

Basically, the Netherlands was under threat. It had just declared its independence from Spain in 1581, forming the Dutch Republic. Quite an ambitious move, considering that the Spanish had the force of half of Europe behind them at the time.

READ MORE | India and the Netherlands in the Age of Rembrandt: exhibition at CSMVS in Mumbai

Given this vulnerability, you can see the advantages of drawing wealth from outside the tiny Dutch Republic and using it to shore up the newly established country against foreign control (while, of course, controlling other countries — but we’re not talking about morality or even ideological consistency here).

The VOC created the shareholding system (and also global capitalism)

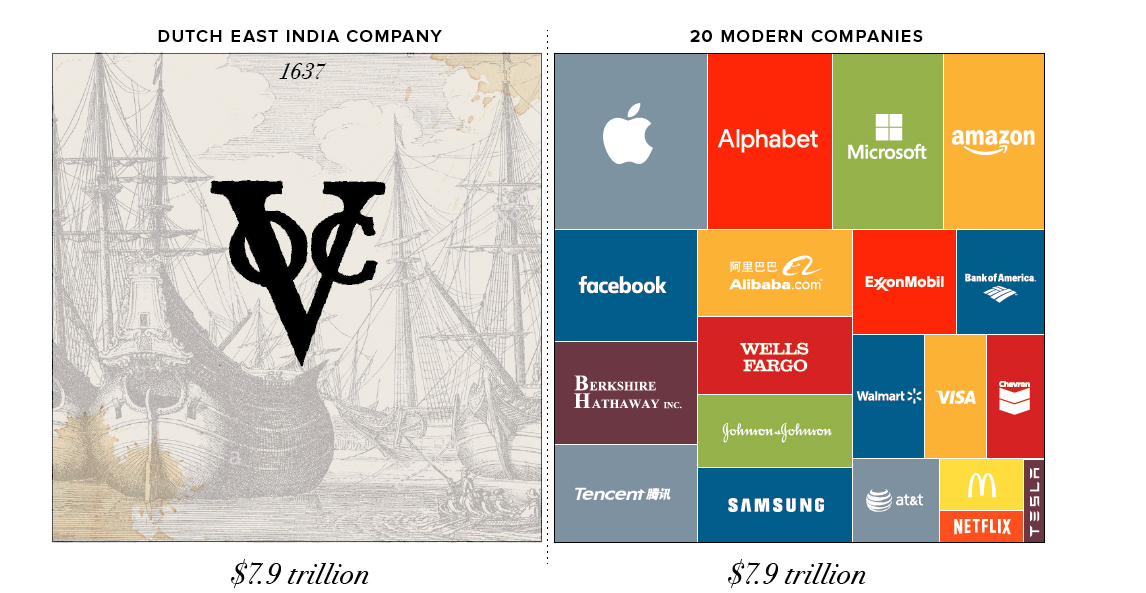

The VOC is considered the first modern multinational company and first made use of many of the features we associate with modern corporations: think shareholders, corporate identity, legal personhood, etc.

This collection of innovations meant that the VOC could mobilise wealth in a way that only monarchies could before, giving it unprecedented power.

READ MORE | The Dutch East India Company was richer than Apple, Google, and Facebook combined

The VOC was also innovative when it comes to acquiring this wealth. It formed Amsterdam as the financial capital of the contemporary world, by allowing public members to invest in the company (rather than in things the company was doing).

The VOC and war

Of course, a massive company like the VOC attracts attention — and because of its dominance in international trade, that attention was mainly negative.

It got into conflict with the British East India Company for obvious reasons: they were both going for the same thing.

Because of the weird space that the VOC occupied — part company, part state — its trade objectives often aligned with military goals.

For example, in 1667, when the Treaty of Breda was signed, ending the war with Britain, the VOC acquired sole control over the nutmeg trade.

READ MORE | The Dutch ship that disguised itself as an island during World War II

Wars also played a role in the colonisation of different areas. In South Africa, a prolonged, low-level conflict with the local Khoikhoi population eventually resulted in the Khoikhoi society breaking down and expanding European settlements in the area.

There were also three wars between the VOC and the Javanese in Indonesia, and in 1641, the VOC took control of Malacca from the Portuguese.

The VOC and colonisation

One of the problems with the VOC is that people in the Netherlands aren’t sure what it was. A business? A force for colonisation? A slave-trading enterprise? A force for bureaucracy in the world? The truth is that it was all these things and more.

The Dutch East Indies: what did the VOC do?

Colonisation in the Dutch East Indies is an intriguing topic because when you boil it down, “true” colonisation of the area only began once the VOC failed financially and was nationalised in an attempt to save it.

Territories that had belonged to the VOC became part of the Dutch Republic’s territory — but this doesn’t mean we shouldn’t consider the colonisation that was taking place before the nationalisation process.

For example, the VOC grew cash crops in Jakarta in the early seventeenth century (then known as Batavia by the Dutch).

This was a clear move from trading spices to growing crops. That way, they could also profit from land that was not theirs. The VOC also took over the surrounding territory to safeguard these crops, increasing their power in the area.

By the late seventeenth century, the VOC had become deeply embroiled in the internal politics of Jakarta, despite their initial intentions not to get involved in domestic affairs.

They encouraged divisions between the different kingdoms in the Indonesian archipelago (again, you’ve undoubtedly heard of the phrase ‘divide and conquer’ before) and took part in two wars against the kings of Mataram and Banten.

After the VOC collapsed in 1800, the trading posts and colonies in the Indonesian archipelago became nationalised as the Dutch East Indies.

How the VOC colonised South Africa

In the Cape, colonisation took place over almost two centuries.

First, Dutch settlers in South Africa were outnumbered by the local Khoikhoi population — for context, there were 200 Europeans and about 20,000 Khoikhoi. So the Khoikhoi initially didn’t have much of a problem with that.

The Cape acted much more as a trading hub than a colony. Slowly, though, the VOC’s plans for expansion became apparent: their transportation of slaves to the colony was just one symptom of their plans to settle a large colony of Europeans there.

READ MORE | The Dutch and South Africa: more than just Apartheid and Boers

In the 1660s, conflicts broke out between the Khoikhoi and the Dutch, and the Dutch burghers expanded their farms outwards. But in 1713, 90% of the Khoikhoi were killed by smallpox.

By the end of the eighteenth century, Khoikhoi society had disintegrated, and 20,000 Europeans were living in the Cape. In 1795, the British ceded the territory when Napoleon invaded the Netherlands during the Napoleonic Wars.

At the end of the wars, the Netherlands formally handed over the Cape Colony to the British, whose colony it remained a part of until 1931.

The VOC and slavery

The VOC also took part in slavery and slave trading during its two hundred years of activity. It exploited workers in the East Indies, sometimes engaging in slavery from its inception. However, its use of slaves picked up when it took control of the Cape in South Africa.

READ MORE | The life of the slaves in the Dutch colonies

After realising that the backbreaking work of settling would need to be done by slaves, the VOC deliberated over enslaving the local Khoikhoi population, even though it vastly outnumbered them.

When they determined that if they annoyed this group, they could easily be kicked out, they decided instead to import slaves from Mauritius and the Dutch East Indies.

VOC slavery in the Cape

For much of the seventeenth century, the number of slaves in the Cape remained low — about one thousand at a time. Slaves mostly were taken from Ceylon, Madagascar and Malaya.

READ MORE | 7 things the Dutch don’t talk about, but should

Because the population was mostly male, it was constantly renewed with new slaves. In the eighteenth century, this number jumped to about 17,000 as the international slave trade increased.

Most of the slaves in the Cape came from either East Africa or the VOC’s territories in the Dutch East Indies.

VOC slavery in the Dutch East Indies

Slavery was also part of how the VOC operated in the Dutch East Indies, but the story there is more complicated.

In their operations in South Africa, the VOC specifically transported slaves from other regions to exploit while building their colony. The VOC mainly used local slaves or slaves from the area in Asia.

On top of that, some of these slaves would have been already enslaved by their local community.

But the presence of the VOC heightened the demand for slave labour, so just because slave labour was part of life in some Asian countries before their existence, the VOC is not absolved of guilt.

How the Dutch East India Company ended

Given that the VOC was so big, you would imagine that its end would have been quite catastrophic to the status of the Netherlands worldwide.

You might also wonder what happened to this company to make it collapse in 1800 — after all, controlling a lot of the spice trade gives a company a fairly hefty advantage.

Commercial problems in the VOC

There were many problems with the VOC’s operation in Asia — some of which did work in its favour in the beginning. However, as time progressed into the eighteenth century, cracks began to show in the VOC’s commercial prowess.

One problem was that it brought all the goods it traded between Asia and Europe first to its trading posts in Asia to be sorted or stored.

This was an advantage for the VOC at the beginning of its trading journey because it had had a better understanding of Asia commercially in a centralised place than its competitors did.

READ MORE | 7 amazing facts about the Netherlands (that you may not know!)

However, it also meant that other companies were making faster journeys and providing fresher goods. For example, the British East India Company would trade directly between Europe and, for example, China.

The Dutch East India Company staff

Another problem was its staff. The VOC was, frankly put, a terrible employer. Like many modern-day multinational companies, it offered low wages.

Not only that, but it also forbade its staff to engage in private trading, meaning they had no opportunity to increase their wages legally.

READ MORE | Lessons about Dutch colonisation should be mandatory, committee finds

Of course, many of them did: the VOC suffered huge amounts of corruption among its employees, mostly because making the journey to Asia wouldn’t have been financially worth it for them without this extra income.

The financial bounty had to be good because we’re talking about a fairly dangerous time for travelling the world. War, illnesses, malnutrition, and some nice venereal diseases killed plenty of VOC staff.

The VOC did not understand maths

Finally, there was a mathematical problem: the VOC paid its shareholders dividends over the profits they made from 1730 onwards.

Let’s say that again: the VOC decided to pay its shareholders more than it made. We are not businesspeople, but this is unequivocally a bad idea.

What this meant in practice was that the VOC did not have enough liquidity to finance its operations for the last seventy years it was active — it relied on short terms loans to do so. Eventually, things would have to change.

The VOC and war

And they did, but not in the way the VOC might have hoped. In 1780, the fourth Anglo-Dutch War began, and half of the VOC’s fleet was destroyed.

The war weakened the VOC’s control of the Asian trading posts. The VOC was a complete financial mess after the war. As was the Dutch Republic, which didn’t exist for almost thirty years after the Anglo-Dutch War ended.

READ MORE | Photo report: the Netherlands at war, 1940-1945

From 1799, the VOC’s contract was not renewed, and it ceased to exist. After the Congress of Vienna in 1814, some of the Netherlands’ territories in Asia were returned to it, and these became colonies of the Netherlands.

Reception in Dutch society now

The VOC was a huge part of how the Dutch Republic functioned for almost two hundred years. Today, it affects the national image of the Netherlands, what we have in our museums, and what lines the national coffers.

The “VOC mentality”

As we move into an era where colonialism is (thankfully) viewed as a negative thing, the image of the VOC in the Netherlands has become complicated and fraught with conflict. In 2006, the then-prime minister Jan Pieter Balkenende coined the term “VOC mentality” in a speech about Dutch commercial thinking and innovation.

READ MORE | The Dutch and their monarchy, a two-sided coin

Many people were offended by this association of the VOC with purely positive characteristics, without acknowledging the harm it caused over its two centuries of operation.

Dutch colonialism in society

In general, the Netherlands’ colonial history has received much attention over the last decade. From the annual Zwarte Piet debates to the Mauritshuis’ decision to take down its colonial founder’s bust, the country is (very) slowly coming to terms with its past.

READ MORE | Decolonising Dutch museums: stolen heritage to be returned?

Museums have begun returning stolen objects to their countries of origin. Universities have started the complicated process of decolonising their curricula, and the Amsterdam Museum has decided to drop the phrase “Golden Age” from its permanent exhibition texts. The relatives of colonial victims in Indonesia have been heard in court.

The Dutch Golden Age: fool’s gold

Part of the reason this reckoning is taking so long is that for a lot of Dutch people, the VOC’s trading prowess coincided with, and in part caused, the “Golden Age” of the Dutch Republic to occur.

This was a time when a very small country held superpower status over much of the world and fended off its much larger and better-equipped enemies in Spain by controlling other parts of the world.

READ MORE | The Amsterdam Museum drops “Golden Age”; Rijksmuseum will retain it

And in a world where global power is still glamorised and coveted, it is understandable (though not excusable) that many people want to hold on to the memory of the VOC nostalgically.

List for further reading

- Dutch Colonialism, Migration and Cultural Heritage – Gert Oostindie

- Dutch South Africa: Early Settlers at the Cape – John Hunt

- Four hundred years on: the public commemoration of the founding of the VOC in 2022 – Leonard Blussé

- The VOC and the exchange – Henk den Heijer et al.

- Batavia: Een koloniale samenleving in de 17de eeuw – Hendrik Niemeijer

What did you already know about the VOC? Let us know in the comments below!

Good article!! After reading it, I was thinking that it might be a nice addition to add a few paragraphes on the VOC/NL in Japan and how that relationship unfolded, as it is quite different how that situation unfolded

There is a awesome, old, 14 episode Dutch (English narrative) documentary ‘Dutch Overseas’ about VOC ON YouTube:

https://youtube.com/playlist?list=PLPqsqhlXd-d6HcVbreG143jVJKPWBlsC3

Great article! Thank you for sharing with a part of awesome Dutch history.

Great article. As a man, born in South-Africa under Dutch parents, this is very intriguing. My dad had the typical VOC mentality, and I hated it. Pure narcisist. As long as he faired well, he was happy. When I asked him why he never gave our gardener a Christmas bonus, he’d say, none of his kind get one. ANyway – Is there any way of a rough calculation of how much the dutch stole from other cultures? How much that increased their own progression, and how much it put back progress of the countries robbed? The common dutch person thinks their country is the best, super proud – and then I always think ‘yeah, made up of theft, rape and slavery – well done buddy’.

Sure, we all have a tendancey to selective memory, but some have more talent in it than others. Also some cultures. I hope to hear from you, that would be great.

Greetings, Arlin Lagendijk

Well said! Although it’s not entirely fair to look at the past through today’s eyes, our colonial history isn’t something we should be proud of

Slaves from Mauritius? Mauritius was uninhabited. Technically, the Dutch are the indiginous people of Mauritius.

Like the Portuguese before them, the Dutch abandoned Mauritius in 1710. They cannot be considered ‘indigenous’ inhabitants (look up the meaning of ‘indigenous’)

onzin

That was very informative. I read somewhere that when the VOC ended it didn’t really end. It morphed into what we now know as Unilever. When I researched Unilever I found that they have a very good, positive PR profile. I don’t see any information about this historic connection, and I can’t seem to find the original source anymore. Has anyone else one else ever heard this information? And if so, can it be substantiated?

saya penasaran ideologi apa yg dipakai waktu itu.

Our ancestors provided substantial wealth to our present day attitudes in many different aspects of who we are as people…World opinions create embarrassing guilt that is all in our minds…Live as good people and forget the past…We are all deserving of a wonderful life…Sharing our goodness is relevant to being happy and secure in our beliefs…I personally love Amsterdam and the local people…I call Amsterdam the World Center of Tolerance…My experiences with Dutch society have been rewarding and satisfying to many of my appetites..Thank you my Nederland brothers and sisters for being on this earth…I would love to hear from anyone of you …We are on this earth to learn about love and to share our knowledge…Until That Moment…